For lovers of racing, little compares to an afternoon (or evening) at the track. The sport is best experienced in the flesh, and the world’s race courses offer diverse ways to enjoy this pursuit. While we can’t literally transport you to the races, we’ll do our best to bring these tracks to you in a regular series of profiles. Today, Sean Magee begins a four-part look at York Racecourse in England by tracing its unique history.

Read about York's quality racing programme

Read about what's in store for a day at York

Read the inside story from the man at the helm

----------

York is indisputably one of the world’s great racecourses.

Located on the Knavesmire, a huge expanse of common land on the edge of the city of York, it provides today’s racegoers with highly modern facilities while having due respect for its centuries of history.

It stages a top-class racing programme headed by three G1 contests at the Ebor Festival Meeting in August, and in 2016, it was second only to Ascot in terms of average prize money per racing day on British racecourses.

It offers horses a flat, wide, and fair track with long stretches that minimise the chance of interference in running.

And not least, it serves a competitively priced house Champagne.

HISTORY

Racing historians like to locate the beginning of equine sport at York as far back as A.D. 208, and to no less a personage than the Emperor Septimius Severus, who had come from Rome to quell disorder in this remote outpost of the empire. To make amusement for his troops at the garrison of what the Romans called Eboracum, Severus brought over a quantity of Arabian horses and arranged for the staging of races on the stretch of land outside the city walls, now called the Knavesmire.

The more recent history of racing at York includes a record of a regular fixture in the 16th century in the nearby Forest of Galtres; King Charles I attending races on Acomb Moor in 1633; and races staged at Clifton Ings, on the banks of the River Ouse, in the early 18th century.

Queen Anne was the first monarch to race her horses at York, where in 1711 – the year she founded Ascot Racecourse – she presented a gold cup worth £100. In July 1714, Anne’s horse Star won a £40 plate at York – but by the time news of her win had reached London, the Queen had died.

A perennial problem at Clifton Ings was the state of the ground, for the Ouse was prone to burst its banks, and in 1731, racing at York was relocated to the Knavesmire, where the ghosts of Severus’s soldiers still raced across its vast expanse, and where public executions had taken place since the late 14th century – hence (though some philologists have other ideas) “Knavesmire.”

The first race on what may be considered the current York racecourse was a King’s Plate of 100 guineas on Aug. 16, 1731, the first day of a six-day meeting. On the morning of that first day, three convicted robbers had been executed on the infamous public gallows situated near what is now the Ebor Handicap start and known as the “Three-Legged Mare:” three wooden uprights positioned to form a triangle, with horizontal wooden beams connecting the top of the three posts, from which the miscreants were hanged.

Most famous criminal hanged on the Knavesmire was the highwayman Dick Turpin, who went to meet his maker on April 7, 1739. A witness described how Turpin “went off this stage with as much intrepidity and unconcern as if he had been taking horse to go on a journey.”

It is a nice conceit to imagine that, after the execution of Dick Turpin, the rabble crossed the Knavesmire and enjoyed a leisurely day’s racing, thereby taking to extremes the great tradition of race meetings providing ancillary entertainments (such as rock concerts nowadays).

But such a notion is undermined by the fact that there is no record of a York meeting that day in the racing calendar, which 12 years earlier had started providing “An Historical List, or Account of all the Horse-Matches Run, and of all the Plates and Prizes run for in England (of the Value of Ten Pounds or upwards).

That parenthetical phrase regarding “Ten Pounds or upwards” offers a lifeline for those who find the idea irresistibly appealing, as that day there might have been lowly races that were not recorded.

Public executions continued on the Knavesmire until 1801, and nowadays the position of Tyburn, as the York facility was known after Tyburn in London, where executions had also taken place, is marked with a commemorative stone. Mercifully, the Three-Legged Mare has long since disappeared.

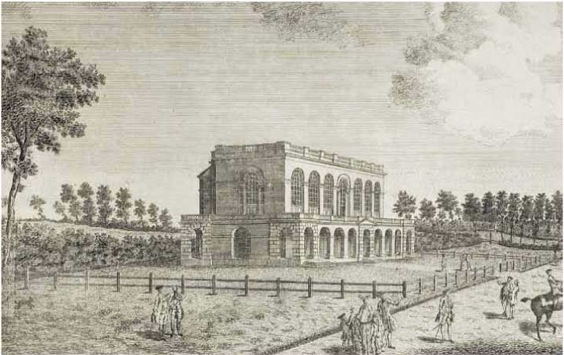

York’s racing reputation steadily grew, and a mark of that status was the erection of a magnificent new grandstand, designed by John Carr, in 1756 – the first permanent racecourse building on the Knavesmire, and the model for similar buildings at other racing venues in the second half of the 18th century.

In their book Racecourse Architecture, published in 2013, Paul Roberts and Isabelle Taylor stress the importance of the Carr grandstand in the history of building for any sporting occasion: “This was not merely York’s first grandstand, nor was it only the first grandstand of any Thoroughbred racecourse, but – in the modern sense of the building type – it was the first grandstand of any sporting venue anywhere in the world.” Yet another historical landmark for York.

The following decade saw the racing careers of two of the all-time giants of the turf, both of whom ran at York.

The little grey Gimcrack won 26 races and was immortalised in some of George Stubbs’s greatest paintings as well as in the Gimcrack Stakes, top 2-year-old race of York’s August meeting – though ironically, Gimcrack was beaten on the two occasions he raced at York.

An even greater racehorse was Eclipse, who on Aug. 20, 1770 walked over (that is, no other horse took him on) for a King’s Plate at York worth 100 guineas, and three days later returned to the Knavesmire to beat two rivals, one of whom bore the unpromising name of Tortoise.

On the human front at this time, much was done to organise York racing by the Marquess of Rockingham, who was twice prime minister (1765-6 and again in 1782) and has a special place in equine history as owner of the racehorse Whistlejacket, subject of the unforgettably enormous portrait by Stubbs that now hangs in the National Gallery in London. (A huge copy of the painting is on display at York Racecourse.)

Possibly not unconnected with the discontinuation of the grisly sideshow of Knavesmire executions, racing at York went into a decline in the first half of the 19th century, allowing Doncaster Racecourse, at the southern end of Yorkshire, to overtake it in sporting esteem. To halt this downward trend, the York Racecourse Committee was formed in 1842 to run the course on more efficient and businesslike lines than hitherto. (Now part of York Racecourse Knavesmire LLP, the Committee continues to run the course.)

The founding of the Ebor Handicap by clerk of the course John Orton in 1843 contributed to the revival of fortunes, and before long the well-endowed Ebor was one of the major races in the calendar. Its founding was closely followed by that of the Gimcrack Stakes in 1846.

Another signal of that revival was the great match race in May 1851 between Voltigeur and The Flying Dutchman, run over 2 miles for 1,000 guineas a side – and the most famous match in British horseracing history.

The Flying Dutchman, by then a 5-year-old, had landed the Derby at Epsom and St Leger at Doncaster in 1849, while 4-year-old Voltigeur had won the same two Classics in 1850, dead-heating for the St Leger and winning the run-off. (In those days, dead-heaters did not share the spoils, but had to take part in a rerun over the full distance of the race.)

Two days later, Voltigeur beat The Flying Dutchman in the Doncaster Cup, and the rematch the following spring was the subject of feverish expectation. The task of setting the weights between the 4-year-old and 5-year-old was given to Admiral Rous, a giant of racing history whose calculations of the weight-for-age scale are still, in broad terms, followed today. He declared that The Flying Dutchman, the older horse, should concede 8½ pounds to his rival, the weights carried being 8 stone 8½ pounds (120 ½ pounds) and 8 stone (112 pounds).

The match drew a crowd to the Knavesmire of the proportions that had turned out to witness executions the previous century – the attendance figure is usually given as 150,000 – and they were not disappointed by what they saw: Voltigeur set the pace, but The Flying Dutchman kept close to his rival, and in the final furlong managed to get past Voltigeur and win by a length.

Like Gimcrack before him, although he never won a race at the course, the runner-up in the great match is remembered in one of York’s major races: the Great Voltigeur Stakes.

Jump racing took place at York between 1867 and 1885, but the flat was always the dominant code there, and through the 20th century the course consolidated its position as one the leading British racecourses. Many held that the notion that York was “the Ascot of the north” was misguided; rather, Ascot should be considered “the York of the south.”

The racecourse became a prisoner-of-war camp during the World War II, and when racing resumed in September 1945, the first meeting included the St Leger, as Doncaster, home of that Classic, was not yet ready to return to action.

Since the war, York has managed to modernise stands and facilities and enhance the quality of the racing programme while not sacrificing recognition of its rich history. That balancing of the old and the new was also at the core of English racing’s most glittering occasion, Royal Ascot, so when it was announced in 2005 that the royal meeting would have to leave its Berkshire home while the enormous new stand was being built, York, only a couple of hundred miles to the north, was always hot favourite to provide a suitable home-away-from-home – and it was duly announced that Royal Ascot 2005 would take place on the Knavesmire.

Royal Ascot at York proved an outstanding success, but occasionally even the best-run racecourse has to give best to the unpredictable British weather, and in 2008, York suffered a serious blow.

That year was expected to see the beginning of a new shape to the course’s flagship event, the Ebor Festival in August. Tradition dictated that this star-studded meeting was held over three days – Tuesday to Thursday – but the temptation to have an additional day and attract a large pre-weekend crowd on the Friday proved irresistible. The 2008 meeting was scheduled for four days, Tuesday to Friday, but then unseasonably wet weather intervened. The Knavesmire was severely waterlogged, and the entire meeting was lost. Several of the pattern races – including the course’s three G1 contests – were relocated to other tracks, and the Ebor Handicap run at Newbury as the Newburgh Handicap.

But that was a rare blot on the success story of York racecourse in recent years, and 2014 saw evidence of further renewal, as changes in the northern part of the racecourse were completed. These involved re-siting the pre-parade ring – always a popular destination for racegoers prepared to defer consumption of Champagne in favour of the opportunity to study the horses close up. The major change brought about by this development was construction of a state-of-the-art new weighing room.

Steeped as it may be in history, York Racecourse never stands still.

This article was updated on May 7, 2017

---

Read Part II: A programme that delivers great racing moments