It’s one of a trainer’s worst nightmares. Here’s the scenario:

Lengthy periods of planning and preparation have gone into selecting a prestigious big-race target at a faraway racetrack; ensuring that your horse is at the peak of physical fitness, having overcome any potential negative side effects of many hours of travel and racing in unfamiliar conditions; and complying with all the relevant licensing and quarantine protocols.

At last, the moment has arrived when you can reap the rewards for all that hard work – your charge has arrived down at the start. Now, you think, while Lady Luck may play her part, everything is out of your hands and it’s just down to the talent of your horse and its rider. Except….

Your challenge is derailed before it has begun by your horse either getting upset in the starting gates or, worse still, refusing to enter those gates and being scratched by the starter. Not only is it a wasted journey but, in the most intense spotlight of publicity, you are left looking like a trainer incapable of “training” a horse to enter the starting apparatus, never mind to run fast once its gates have opened.

What promised to be a showpiece triumph, a career highlight worth trumpeting for the rest of your working life, has turned into a public relations disaster.

It has happened. Way back in 1990, a British-trained horse called Pelorus undertook a 6,000-mile flight and was set to become the first European runner in Hong Kong only to refuse to enter the gate.

And, eight years later, Red Sea burrowed his way out of the front of the gates and ran loose for a while before the start of the Breeders’ Cup Juvenile. Although subsequently re-installed, he ran a dull race and finished a distant last but one.

His jockey, Kent Desormeaux, railed against the officials in post-race interviews, while his equally combustible British trainer, Paul Cole, revealed that he had warned the authorities beforehand of the likelihood of a problem if Red Sea was not given special dispensation to load last. Cole labelled the starter “pig ignorant.”

The latest big international race starting gate incident in America was five years ago. It came on the grandest stage of all, the Breeders’ Cup Classic, and proved that you don’t need to be a foreigner to come unstuck with starting procedures.

Quality Road was shipped from Todd Pletcher’s Belmont barn in New York all the way to Santa Anita in California only to get involved in a battle of wills with the gate crew that left him with lacerations on his legs, a bleeding tooth, and a big bruise over one eye.

He was not allowed to run, and thus passed up the chance to gain a share of the contest’s $5 million prize money.

Although the short-term consequence was Quality Road’s refusal to board a plane 48 hours later, hence consigning himself to being driven across America, his later career was not blighted. He went on to win three G1s after schooling sessions with Bob Duncan, a well-known starting consultant in the U.S. who pioneered a natural horsemanship approach to loading horses into the gate when employed as the head starter at The New York Racing Association tracks.

Another horse to go on to great things despite being branded a “rogue” after refusing to enter the starting gates in embarrassingly public circumstances was Spanish Moon, trained in England by Sir Michael Stoute. In 2009, just six months before that Quality Road episode, he refused to enter the stalls at Newmarket for the G2 Jockey Club Stakes, the race before the 2,000 Guineas.

He was banned from racing in Britain for six months because this was his third non-participation incident. A clearly irked Lord Grimthorpe, racing manager to Spanish Moon’s owner, Prince Khalid Abdullah, reacted with the words “we’ll just have to take him to countries where they want him,” and things didn’t work out too badly – he won more than £1 million in five overseas starts prior to his next home appearance.

So how can further such instances be avoided? A tiny minority of Thoroughbreds seem to have a phobia about the starting gates and will continue to do so in years to come.

In Britain, two men, Gary Witheford and Steve “Yarmie” Dyble, have made their names ironing out the kinks in problem horses and often going down to the start with them, while worldwide the use of a special “gate blanket,” designed to stop a horse’s flanks coming into contact with the starting gate (which can prompt claustrophobia) and sometimes called a “Monty Roberts Rug” in reference to the renowned British horse whisperer, has become commonplace.

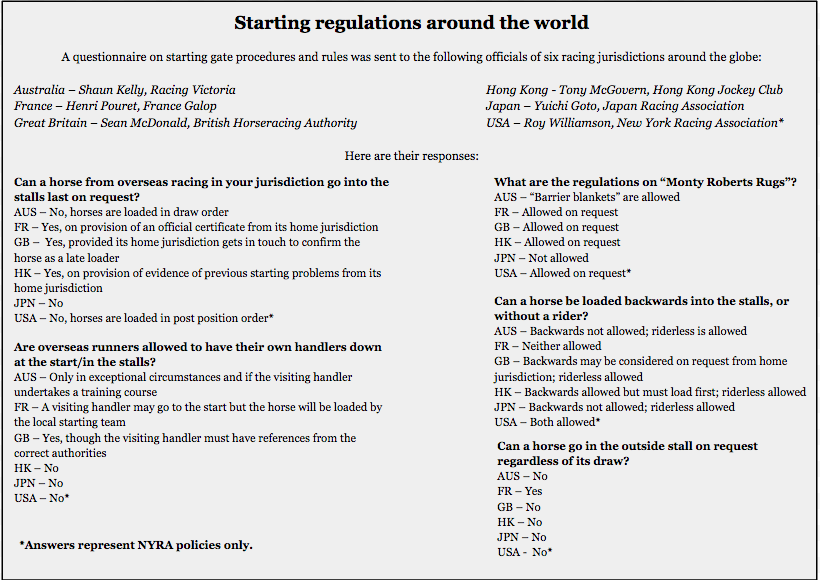

However, local rules vary wildly and some jurisdictions make fewer allowances for problem horses than others.

Spanish Moon’s story is an odd one, as he earned the ban when racing just yards from where he exercises in the morning, so lack of knowledge of the rules and regulations is no excuse in his case.

But ignorance of local starting etiquette is the most likely source of difficulty.

In Britain and France, for instance, the likes of Witheford and Dyble can accompany their “patients” throughout the loading process, whereas in America, Japan, and Hong Kong that is expressly forbidden.

Monty Roberts Rugs are banned in Japan, while in France, which in many ways bends over backwards for difficult horses and allows any horse on request to be loaded into an outside gate regardless of its draw, it is strictly forbidden for horses to be loaded backwards or without a rider.

Most crucial of all is the response of local stewards to a plea for a gate-shy horse to be loaded last. On provision of some evidence of previous problems in their home jurisdiction, such a query will be acceded to in France, Britain, and Hong Kong but not in Japan. Rules can vary by jurisdiction in the United States - post position order is the norm, but loading out of order may be allowed at the starter’s or stewards’ discretion under certain circumstances.

The most extreme case - in distance terms – of a wasted journey would come if a horse from Europe went all the way to Australia, enduring a 21,000-mile round trip, only to be scratched for refusing to load.

Thankfully, this has yet to happen, but one of Ireland’s most recent Aussie raiders, Slade Power, who ran in the Darley Classic at Flemington in November, had not always been a straightforward character in the gates so his trainer, Edward Lynam, took various steps to ensure his previous problems did not resurface.

First he organised for a travelling member of his staff to complete a starting gates accreditation programme with Flemington’s governing body, Racing Victoria, to enable him to load the horse in the Darley Classic.

He then enrolled Slade Power in a voluntary starting gate test, or “barrier trial” as it is known Down Under. This did not go altogether smoothly as both having a barrier attendant in the gates with him and having his regular blindfold removed too slowly upset the Irish visitor.

However, Lynam did well to discover all this before the big race and, following discussions with Racing Victoria officials, on race day Slade Power was allowed to load later than his gate number would normally dictate and his jockey was permitted to remove his blindfold at the precise instant the stalls opened.

The tale does not have a happy ending as, although Slade Power recovered from a slightly slow start to take up an ideal stalking position in the early part of the race, he suffered a muscle injury during the closing stages, and finished 11th of 13 with jockey Wayne Lordan easing him down as they crossed the winning line.

But Lynam does deserves credit for his thoroughness in making sure that an alien starting procedure did not compromise his horse’s chances.

---

James Crispe is Associate Director of Editorial at the International Racing Bureau.