.jpg__760x480_q85_crop_subsampling-2_upscale.jpg)

Few will argue that Australian racing has been besieged by some very specific drug scandals in the last year, and, as the sport seeks to mop up the damage, Jessica Owers looks at the role of penalties handed down. Are they effective at deterring cheats, and should they reflect public opinion?

In a short time, the Australian racing season will draw to a close, wrapping up its wares on the last day of July. Admittedly a year of good, competitive racing, it has also been one punctuated by dogged, damaging drug scandals. In 12 months, the race-going public has brushed up on its high-school chemistry with cobalt headlines burning a hole in the sport, while, more recently, unnerving details have emerged about horses testing positive to methamphetamine. Were racing in a hurry to be done with any year, it would probably be this one.

Of late, the most attention has been pointed at trainer Sam Kavanagh. Based at Rosehill Racecourse, Kavanagh is the son of Melbourne Cup-winning trainer Mark Kavanagh (who is under investigation in Victoria for cobalt charges). The younger Kavanagh has been slapped with 24 individual charges by Racing NSW in recent weeks, relating to positive cobalt swabs, the alleged use of xenon gas, and the administration of an alkalising drench. There are 52 charges associated with this case, dragging six people under, including Kavanagh, embattled Flemington Equine Centre veterinarian Tom Brennan, and disqualified trotting trainer Mitchell Butterfield. It has even bundled up Matt Rudolph, a senior racing executive at the Australian Turf Club.

If cobalt required some concentration on the part of the wider public when it came to grasping its seriousness, methamphetamine required none.

In March, Racing NSW revealed that Scone-based trainer Luke Griffith was under investigation for positive equine swabs to “ice”. Routinely associated as a human street drug, the idea that horses were being administered ice was shocking and irreparably damaging for racing. Griffith was ejected for three years on six charges, with another 12 months on two further charges and, with many believing that a four-year ban was a light sentence, discussion erupted. Are the current penalties in Australian racing fitting the crimes?

The Griffith situation was a case in point.

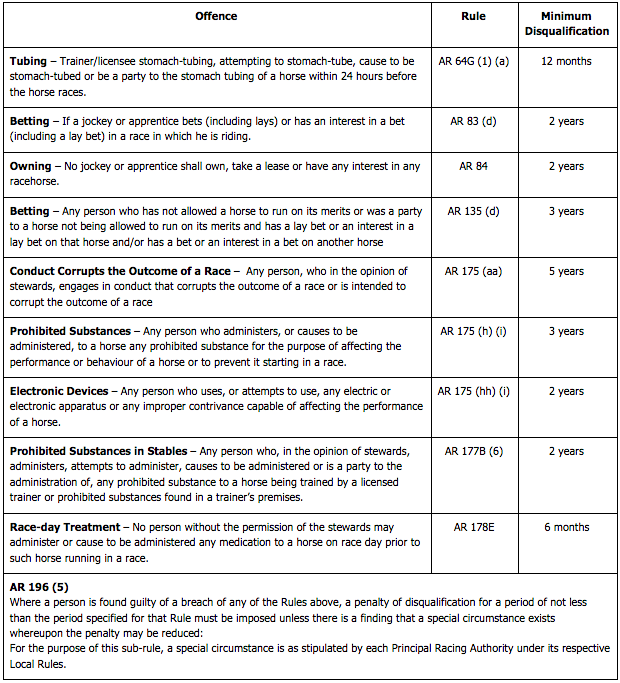

On one hand was a shocked public that knew all too well the frightening, often psychotic effect of methamphetamine and, from an animal welfare standpoint, Griffith’s four years seemed lenient. It was hard to imagine the calibre of person that would give a horse such a thing. On the other hand were New South Wales stewards, bound by the rules of racing pertaining to prohibited substances (rule AR 175 (h) (i), see below). Even as the public cried for blood, and many in the case of Griffith called for a life ban, stewards had to follow the rules.

“I concede that sentencing is often a subjective judgment, and some will always believe that a penalty is too light in some circumstances,” said Peter McGauran, chief executive of Racing Australia. “However, a minimum disqualification of two years for a licensed person is at best severely career limiting, and at worst career ending.”

In November 2012, Racing Australia (then the Australian Racing Board) addressed the issue of penalties head on. It had found that, over time, sentences had been reduced via the appeals process and stewards, who were bound by precedent, were caught in the wheel.

“Suspended and disqualified persons knew they could turn to the civil courts to argue that a heavy penalty was too harsh, and inconsistent with lighter penalties previously given for the same offence,” McGauran said. “We had to break the nexus between precedent and penalties that no longer reflected either industry or community standards. The only way the civil courts would accept heavier penalties was if they were based on new rules outlining minimum penalties, thereby severing the link with precedent.”

The new minimum penalties addressed the most severe offences in racing, and were/are as follows:

As it stands, racing’s governing bodies in each of Australia’s respective states and territories must abide by the above minimum penalties, but each is ultimately responsible for the final sentence handed down to guilty parties. In other words, the stewards at Racing NSW could not have given Luke Griffith any less than the four years he was handed (exempting special circumstances), but they could have given him more, and this is where racing battles with public opinion.

Dr. Craig Suann is the senior regulatory veterinarian at Racing NSW, and has been in the game for almost 30 years. He said it was important to remember that stewards weigh up all the evidence in cases, and some of that evidence doesn’t necessarily reach the public realm.

“In the case of Luke Griffith, it was fairly firmly established that there was evidence of ice use by individuals within the stable, and it’s not beyond the realm of possibility that, if there are human users in the stable environment, there can be contamination.”

As an example, he flags the case of racehorse Love You Honey. Trained by Gai Waterhouse, in 2005 the filly returned a positive swab to a cocaine metabolite, and a subsequent inquiry identified evidence that pointed to accidental contamination by a stable employee or employees. However, regardless of how the cocaine made it into the horse’s system, under the rules of racing Waterhouse was culpable for a positive swab, and was fined AU$15,000.

Suann said that in certain cases, when it comes to determining a sentence stewards will consider if a trainer has a poor track record. If public opinion is anything to go by, this is important for racing’s integrity, which has taken a hit in recent months. Suann said the sheer number of cobalt charges this season, along with the damaging publicity associated with the alleged administration of an illicit street drug, is concerning.

“Racing has always been aware of the reputational risks to the industry, but we’re more aware of it now as the animal-rights groups get better organized and more vocal,” he said. “The broader community is less involved with livestock now. Animals like horses are more remote from day-to-day practices, and racing is having to deal with ever-changing perceptions of how we treat these horses.”

Suann’s point is that modern horse racing has had to evolve with the wider public’s demands for horse welfare, a public that has, in most cases, nil experience with handling horses.

McGauran said racing’s penalties are an essential element in maintaining public confidence. He believes drug testing, surveillance, and intelligence-gathering initiatives result in penalties that not only achieve this, but also deter cheats.

“Racing spends tens of millions of dollars a year on integrity measures to maintain the confidence of punters and stakeholders in fair and transparent racing,” he said. “Integrity is the cornerstone on which racing is built and, along with animal welfare and jockey safety, is our foremost priority.”

It is clear that Australian racing wants to be seen on the front foot when it comes to matters of integrity, and in most cases, it has acted quickly on the cobalt and ice charges. However, neither cobalt nor ice is likely to fall off the carousel soon, and the sport must respond with one eye on the rulebook and another on the public. When it comes to the latter, penalties play a vital role.