FROM THE ARCHIVE: Patricia McQueen’s long-running series following Secretariat’s progeny is one of the most popular items at Thoroughbred Racing Commentary. Here’s where she started out nine years ago

• Originally published November 2015

There’s an old saying in the Thoroughbred industry – breed the best to the best, and hope for the best. For Australian businessman David Hains, that theory produced magic in the name of Kingston Rule.

Twenty-five years ago, the handsome son of Secretariat found the extra firm ground to his liking and won Australia’s famed Melbourne Cup, setting a course record that still stands today.

“Secretariat was the best horse as a racehorse in history, and I believed that a combination with Rose Of Kingston might work,” Hains recalled recently of the royal mating he planned some 30 years ago. After all, Rose Of Kingston was named Australian Horse of the Year at three; her victories for Hains included the 1982 AJC Derby against the boys.

The champion, by the undefeated Italian stakes winner Claude, was one of several mares Hains sent to his Kentucky farm in the mid-1980s. She was bred to Alydar, Seattle Slew, Nureyev and Green Dancer, but it was her 1986 son by Secretariat who would make all the headlines.

The flashy chestnut, nearly a carbon copy of his famous sire, earned the nickname Magic after he was born in Kentucky on March 18, 1986. Officially Kingston Rule, he was sent to trainer Patrick Biancone in France, who had several other horses for Hains at the time.

Although some sources say Kingston Rule had one poor start in France, there is no record of him running in an official race there. The youngster needed time to mature, so he was sent to trainer Tommy Smith in Australia.

How they overcame his fear of other horses

Kingston Rule made his first start at Warwick on May 9, 1989. He finished 13th and last in a maiden race at 1,400 meters, beaten 35 lengths on a heavy, wet course. Smith thought he had seen enough, and recommended the horse be gelded. Hains wasn’t prepared to take that step given the bloodlines, so Kingston Rule was sent back to Kingston Park in Victoria to regroup.

After time on the farm, he was transferred to Bart Cummings’ barn in Melbourne.

He was described as a “raving, ranting bull” who was frightened of other horses and who would break out in sweats, according to Cummings and his then-foreman, Leon Corstens, as recounted by Les Carlyon in his biography of the trainer.

Patience and time were the prescriptions to calm the beast, and the Cummings team had plenty of both. For example, they took him to some of the country race meetings several times – not to race, just to get more experience being around other horses.

Kingston Rule made his first start for Cummings in the Chatham H. at Caulfield on January 6, 1990. He finished second, but appeared to be making a winning run when another jockey’s whip struck him on the head. He broke through with victories in his next two starts, both at Sandown, on January 23 and February 10.

Carlyon described the February appearance as that of a horse on the edge of a nervous breakdown – “He was so highly strung he was close to being unstrung ... It was as though he was waiting for a tiger to jump out and land on his back.”

‘The day we knew he had a big race in him’

Clearly Cummings and Corstens needed to keep working on Kingston Rule. “Too much blood, not enough mongrel,” Carlyon wrote. Hardly the type to win a Melbourne Cup.

After three more starts that fall, he was put away until the following spring, by which time Kingston Rule was starting to “conquer his demons,” noted Carlyon. After two unplaced finishes, he sent a message with a strong fourth-place effort in the 1,600 meter G2 Craiglee S. at Flemington on September 8, 1990, closing 20 lengths in the final half-mile.

“That was the day we knew for sure he had a big race in him,” Corstens said at the time. “It was a colossal performance.”

But he hadn’t yet done enough to be assured a place in the Melbourne Cup, and Cummings continued to tweak the horse’s training regimen. He added rubber shock absorbers under his shoes because he hit the ground hard with his forelegs. To encourage him to stretch out and keep his head down, Cummings added a big shadow roll. And he worked the horse hard, with long morning gallops, time on a treadmill, and even swimming sessions. “He was rather big and overweight in my opinion,” the trainer recalled in 2012.

After two more races, the colt won the 2,600 meter G2 Moonee Valley Cup on October 27, which guaranteed a spot in the Melbourne Cup. But he was blowing a lot afterwards, remembered Cummings. “I monitored him on a daily basis, and decided he’d have to run again before the Melbourne Cup.”

So, with the Cup looming, he ran in the G2 Dalgety at Flemington on November 3, historically a popular spot for Melbourne Cup-bound horses. He finished second, again uncorking a scintillating rally under new jockey Darren Beadman, coming from last to just miss by a half-length over 2,500 meters.

“He needed that race because he was a very heavy horse and it was the only way to clean his wind up,” recalled Cummings. “If you feed them well, the racing doesn’t hurt them. They need it.” And there’s no doubt that Kingston Rule was thriving on the schedule.

He looked so good his odds quickly tumbled

When he appeared at Flemington before the Melbourne Cup three days later on November 6, 1990, Kingston Rule was dead fit, his copper coat glowing. Most importantly, he was relaxed – with none of the nervousness so evident earlier that year. Cummings and Corstens had worked their magic. The horse looked so good that his odds quickly went down from 12 to 1 to 7 to 1, making him co-favorite with New Zealand’s The Phantom.

Early in the race, Kingston Rule settled along the rail, running just behind the first few in the field of 24, never too far back and saving ground almost every step of the way. Beadman eased him out turning for home and hit the front with a furlong to go. As The Phantom made his run on the inside, Beadman resisted any temptation to use the whip, which Kingston Rule didn’t like. He urged the horse on with only his hands and legs and won by a length.

“I couldn’t believe my eyes when I hit the front a furlong out,” said Beadman after the race. “I saw The Phantom come at me on the inside and I hoped it wasn’t him, as I thought he was a good chance, but my bloke was too good.”

Too good indeed. Kingston Rule completed the 3,200 meter race in a record 3:16.3, a time that has never been bettered.

Twenty-two years later, Cummings reflected on the horse, perhaps forgiving him his early antics. “He was a thorough gentleman. If he had two legs, I’d call him ‘sir.’ On a dry track, he was very, very effective, and he was a great stayer.”

Soft ground was his Achilles heel, so that disastrous first start over heavy going was easily explained.

Remarkably, Secretariat’s influence in the 1990 Melbourne Cup was not limited to the winner. Finishing third was the unimposing 6-year-old gelding Mr. Brooker, a son of Kentucky-bred Our Best Friend, a member of Secretariat’s second crop and the first of Secretariat’s sons to end up at stud in Australia.

Kingston Rule had earned a short vacation at the farm, and returned to Cummings’ stable in December with an ambitious goal – the 1991 Japan Cup. “I know what is required of the horse, the trainer and the jockey to win the Japan Cup, and in Kingston Rule I feel I have the right material to take on the best in the world,” Cummings announced at the time.

It wasn’t meant to be. After three starts in early 1991, he bowed a tendon and his racing career was over. He had four wins in 18 starts and earnings of A$1,549,125, plus the celebrity that came from winning one of the world’s most important races as a son of one of the world’s best racehorses.

So it was on to a second career as a stallion with high hopes, despite the fact that stayers weren’t usually popular and rarely received the best mares. He was sent to Ealing Park in Victoria, under the watchful eyes of Tim and Lisa Johnson.

Tim Johnson recalled that it took Kingston Rule a couple of seasons to fully mature and lose that racehorse look. “Then he developed into this magnificent horse – really there was no better-looking stallion anywhere.”

Very easy going at the farm, the horse loved to spend his days sunbathing. “He was too smart to waste his energy,” Johnson said, adding that Kingston Rule exercised just enough to look after himself, so he never got too heavy.

But like other sons of Secretariat, he struggled as a sire. His 1994 crop produced his two best offspring, the very good G1-winning fillies Kensington Palace and Sheer Kingston. In total, he sired 10 stakes winners.

His popularity waned as quality runners were few and far between, and he bred just a handful of mares annually in his later years.

“To have such a good-looking horse with such a good pedigree, it was a crying shame that he wasn’t more successful as a stallion,” said Johnson, who considered Kingston Rule part of the family at Ealing Park until the horse died from the infirmities of old age on December 3, 2011.

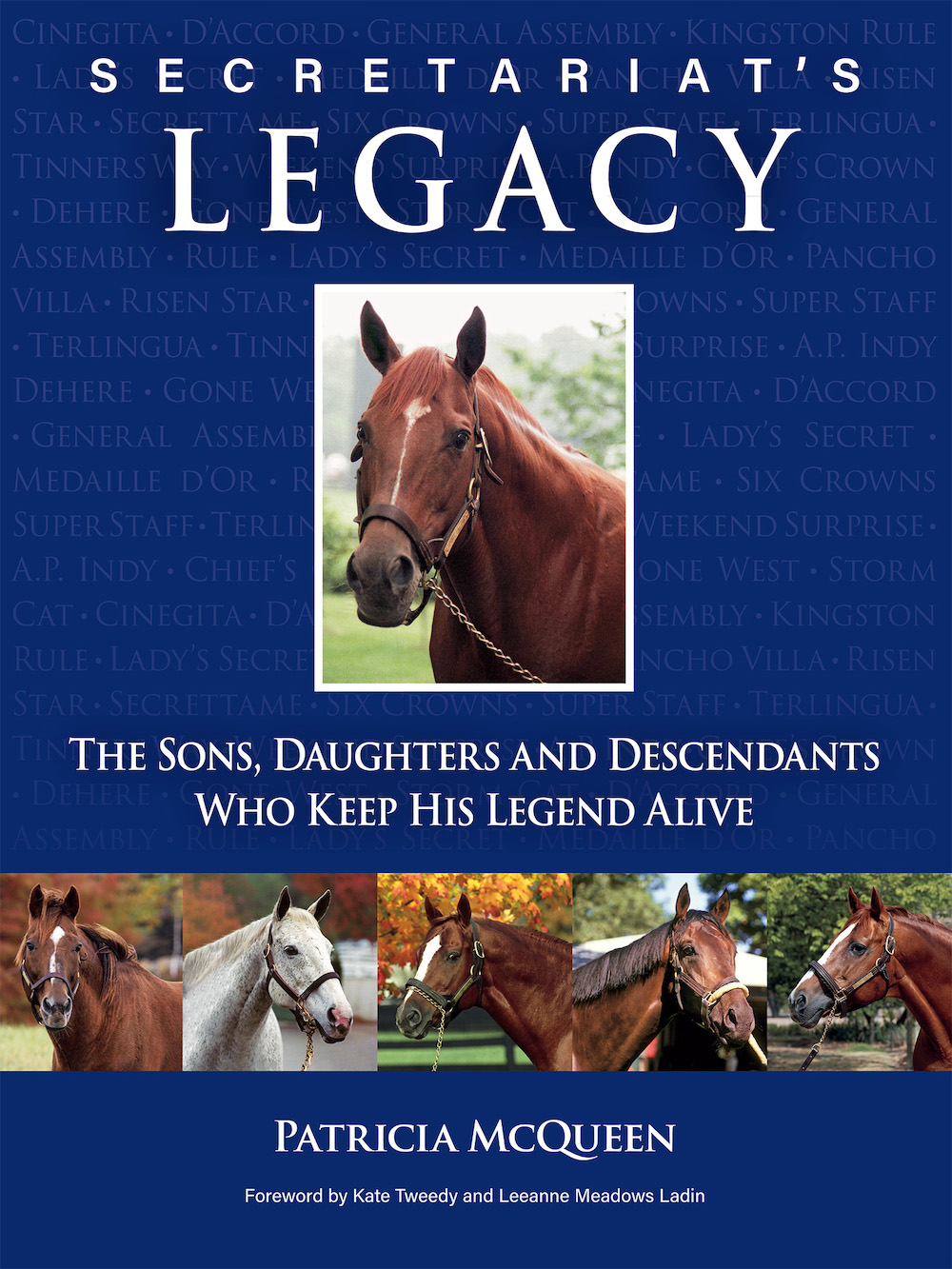

Secretariat’s Legacy by Patricia McQueen can be ordered here for $54.95 at secretariatslegacy.com

Secretariat’s Legacy by Patricia McQueen can be ordered here for $54.95 at secretariatslegacy.com

The road less traveled: how Secretariat’s sons left their mark in Italy, Hungary and Switzerland

More than just a US phenomenon: how Secretariat’s progeny fared in Europe

Last of the family line: catching up with Maritime Traveler, the only living son of Secretariat

View the latest TRC Global Rankings for horses / jockeys / trainers / sires