The Thoroughbred racing industry in the United States is not exactly known for its commitment to record-keeping. While that has changed in the last few years, thanks to access to online databases and digitally archived newspapers, digging for information on horses before 1991 (the year in which access to free online charts became available) is an arduous, old-school, analog endeavor.

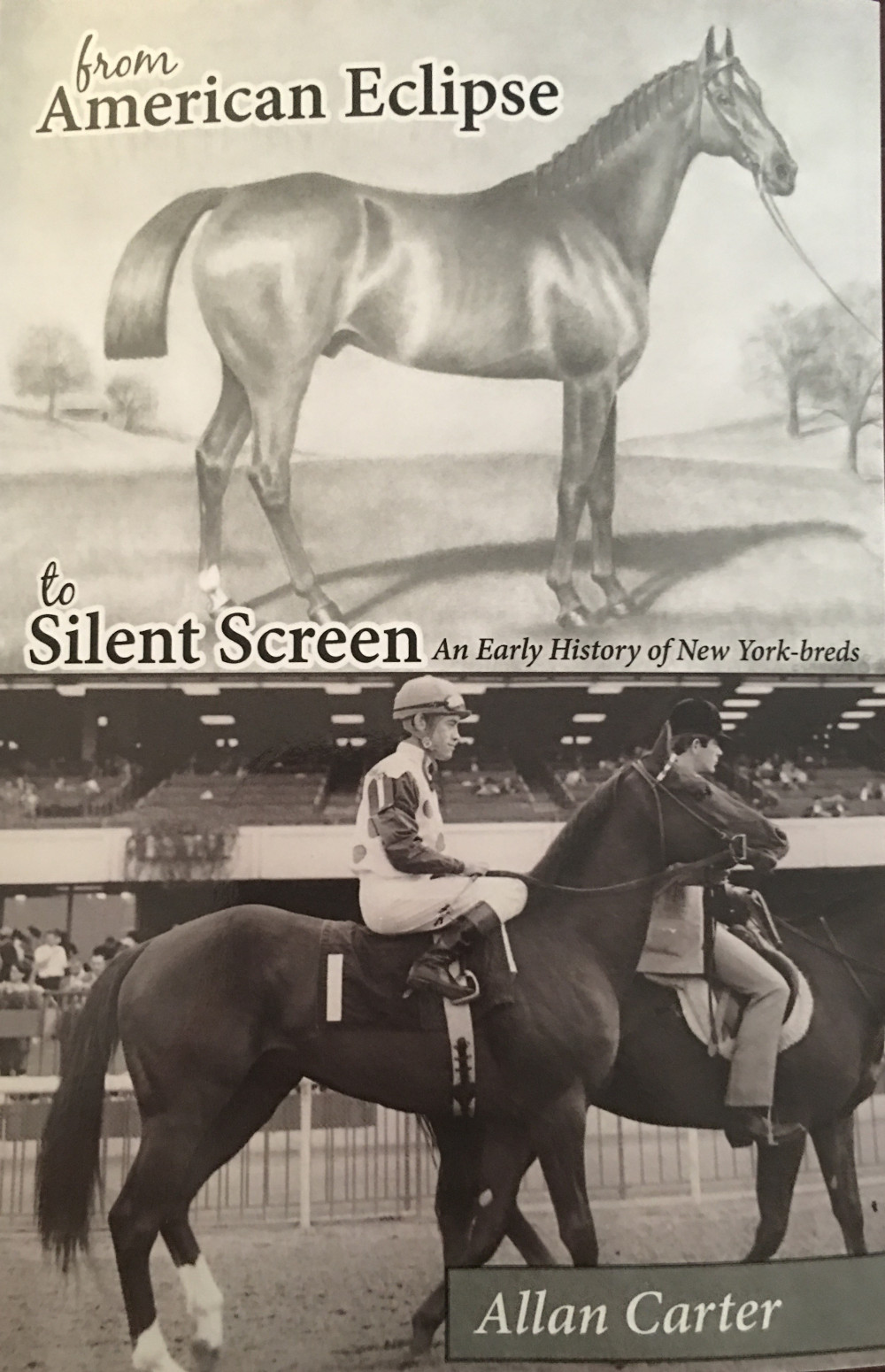

None of that deterred Allan Carter, the former New York State Law Librarian and current volunteer historian at the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame in Saratoga Springs, who last year published From American Eclipse to Silent Screen: An Early History of New York-breds.

None of that deterred Allan Carter, the former New York State Law Librarian and current volunteer historian at the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame in Saratoga Springs, who last year published From American Eclipse to Silent Screen: An Early History of New York-breds.

“A couple of years ago, [turf writer] Mike Veitch and I were talking about New York-breds,” said Carter by phone from his Saratoga home. “There was no way to tell who was a New York-bred and who wasn’t.”

Now, of course, past performance data in the United States include the state in which the horse was bred, though the definition of that can vary by state. In New York, a foal’s status is determined by the mare, whose status falls into two categories. All New York-bred foals must be born in New York State; if the mare is a resident of New York State, she must have been in the state continually from within 90 days of her last cover in the year of conception until she foals the following year.

If the mare is not resident, she must remain in New York for 90 days after foaling, and be bred back within that time to a registered New York stallion. These conditions must be met in order for the foal to be considered part of New York’s lucrative state-bred racing and breeding program.

Click here for full details of the New York owner and breeder awards

But go back a hundred years, and where a horse was bred was largely insignificant. One might ask, then, why Carter wanted to uncover that information.

“I always need a project in the winter,” he said. “I wasn’t even thinking about publishing it, but I got really intrigued when I found out that Glenelg was a New York-bred.”

Foaled in 1866, Glenelg was second in the 1869 Belmont Stakes before winning that year’s Jerome and Travers Stakes.

Intrigued, Carter began putting his research chops to work, exploring the digital archives of the Daily Racing Form and The New York Times, along with an archive of current and past New York State newspapers.

He discovered that, in 1866, a Roderick W. Cameron purchased from England a mare called Babta, in foal to Citadel. The foal was born in the New York City borough of Staten Island — not ordinarily considered the birthplace of champions. August Belmont, a breeder himself and the man for whom the Belmont Stakes is named, purchased the foal, to be named Glenelg, for $2,000.

“Nobody really cared that much about it back then,” observed Carter. “People didn’t start talking about New York-breds until the early 20th century.”

According to Maryjean Wall’s How Kentucky Became Southern, New York State was the center of the U.S. Thoroughbred breeding world roughly from the end of the Civil War in 1864 until the turn of the 19th century, when Kentucky reclaimed that stature, and New York fell out of favor as a place to breed horses.

As Carter’s interest grew, he began to uncover stories not just of important New York-bred horses, but of the men and women who based their breeding operations in the state, from Long Island in the southern part of New York to further up in the Hudson Valley.

“Kentucky doesn’t have the greatest climate,” he said, “but it shocked me that you could even breed horses back then when temperatures were below zero. It turned out that you don’t need the bluegrass to breed horses.”

Sanford’s mission

Carter credits Sanford Stud, which was located about 30 miles outside Saratoga, with having the biggest impact on New York-breeding. Established by Stephen Sanford in the early 1880s, it produced important, accomplished horses until the second decade of the 20th century. In 1913, the Sanford Stakes was established at Saratoga in the farm’s honor.

“He really had a mission to prove that you could breed horses in New York, and he did it,” said Carter. “It was a matter of pride for him; he was born and grew up in New York, and he wanted to prove that you could produce good horses here.”

Among the New York-bred names featured in the book are Aristides, winner of the first Kentucky Derby, who was conceived in New York and born in Kentucky; Ruthless, the filly who won the first running of the Belmont Stakes; and Sally’s Alley, the filly who won the 1922 Belmont Futurity, at the time the richest race in the country.

Carter’s book was supported financially and promotionally by New York breeding organizations and published by Northshire Books, an independent bookseller with a location in Saratoga Springs.

“We try to support local authors any way we can,” said Debbi Wraga, Northshire’s publishing coordinator. “Allan is a local, and he’s writing about the heart of Saratoga. How could we not want to be involved?”

“Talk to him for even two minutes, and you want to listen to him for hours,” she continued. “He makes you want to read the book and learn the history. He’s got knowledge beyond knowledge.”

“Allan Carter’s new book is an engrossing history of New York-breds before there was any such thing as a ‘New York-bred’,” said Jeff Cannizzo, executive director of the New York Thoroughbred Breeders in a statement. “It is absolutely a must-read for everyone interested in the evolution of Thoroughbred breeding in the U.S.”

Filling a vacuum

Though the book hasn’t been purchased as enthusiastically as Carter had hoped and despite the challenges of tracking down information between 1973 and 1991, he has begun to do some tentative research on New York-breds in recent decades, a timely project given the recent successes of the breeding program. Earlier this month, New York-bred Audible won the G2 Holy Bull, a key Kentucky Derby prep, at Gulfstream Park in Florida; New York-bred Bar Of Gold won the G1 Breeders’ Cup Filly and Mare Sprint last November; Dayatthespa was voted Eclipse Champion Turf Mare in 2014 and La Verdad was the champion female sprinter of 2015.

From American Eclipse to Silent Screen is the first book devoted solely to tracing the history of New York-breds, and it is organized chronologically by breeder. Its index includes all the humans and horses mentioned in the book.

“I can never get over the thoroughness of Allan’s research,” said Bennett Liebman, government lawyer in residence at Albany Law School and former deputy secretary for racing and gaming in New York, himself an authority on New York’s racing history. “He is fixated on getting the research absolutely right, and he has produced a book that has filled a vacuum in our knowledge of New York-breds.”