FROM THE ARCHIVE: Amanda Duckworth with an account of a joyous Louisville gathering celebrating the legacy of African-American racetrackers

• Originally published December 2019

At the urging of Ms Sylvia, retired jockey Sam Alexander stood in front of a packed crowd at Syl’s Lounge, a beloved Louisville bar, and told his story. The room was a mix of lifelong friends who might as well be family and friendly strangers eager to hear about his life.

Ms Sylvia noted Alexander is the quiet sort as he was given the microphone, and, although he was uncomfortable in the spotlight, it was also clear that ‘no’ simply isn’t a word Ms Sylvia has accepted throughout the course of her life.

Alexander’s words were no less impactful for the soft and gentle way they were delivered, until, eventually, overcome by emotion, he suddenly handed the mic back, and walked out the front door into the brisk night.

His story is not in the recently released book Better Lucky Than Good: Tall Tales and Straight Talk from the Backside of the Track, but Ms Sylvia’s is.

Compiled for three years by the Louisville Story Program, the book was written by 32 people who have lived, worked and otherwise been a part of the backside at Churchill Downs. Its organizers wished they had additional time to gather even more of the rich history that is so rarely discussed in the public realm.

However, like Douglas Park, the mostly forgotten Louisville racetrack that used to coexist with Churchill Downs, so many of racing’s characters have faded from the official record.

Rich in thought

The event at Syl’s Lounge was meant to specifically celebrate the legacy of African American racetrackers in Louisville. It was an opportunity for those in the book to gather and tell their tales, and it also provided a chance for those like Alexander who still had a story to tell to tell it.

Ms Sylvia, officially Sylvia Arnett, is now in her 80s, but she grew up in the shadow of Churchill Downs, one of 11 children. Kids in the neighborhood learned to follow the horses from a young age, and she was a quick study.

“When we were kids, we would park cars, and we thought we were making big money getting a quarter to watch a car,” she said. “Later on, we learned to pool our little bits of money. There were racetrackers that came from out of town, and they always had good hunches. We would send our money over with an adult, and betting became an option at an early age.

“We learned to read the program, and we could tell you all about a mudder or whether a horse was a filly or gelding. Racing was in your blood. If you were from South Louisville, the racetrack was it.”

Horses stayed with Ms Sylvia throughout her life. Her brother-in-law, Jacob Bachelor, worked oiling machinery at the local International Harvester Plant, but he also loved horses. He saved up extra money by hauling furniture for Green Company, and he eventually became an owner and a trainer. In 1972, he won the Debutante Stakes with a filly named Sylva Mill, who was named after his wife, Mildred, and Sylvia.

Then, in 1975, one of Bachelor’s horses, Naughty Jake (who was named after the trainer himself), won the Spiral Stakes, finished third in the Derby Trial, and could have competed in the Kentucky Derby. Bachelor opted not to run him because of the money he would have had to pay to enter. Sports Illustrated even published an article called The Horse That Almost Ran because having an African American owner-trainer, especially then, was so remarkable.

“We wanted him to run the horse in the Derby,” said Ms Sylvia. “We thought he had a heck of a horse, and he would have gotten there. But he wasn’t sure he was good enough, and you had to have a large sum of money to enter the horse. We didn’t do it, but we thought if we had went around the neighborhood collecting money, we could have gotten that horse in, and we would have had an African American Derby trainer and owner.”

Ms Sylvia and her late husband, Johnny, began owning horses themselves in 1976. Although they had claimers and not stakes horses, they still had a good time with their small stable.

“We would be in the paddock, and once you had a horse and the neighborhood heard about it, you didn’t have to worry about it,” she said. “Everybody in the neighborhood would be over there at the paddock to see if what they were hearing was really true.

“So many times, we would go to the smaller tracks and you would hear people say, ‘Those African American people over there, they own that horse! They are getting ready to run that horse!’ We thought we were real celebrities. We were poor, but we were rich in thought.”

When Ms Sylvia’s husband retired from Ford, they decided to stop owning horses in order to open a local bar. They bought a club, renamed it Syl’s Lounge, and it will celebrate its 30th anniversary in 2020.

Pass the mic

Standing in Syl’s Lounge, the first thing Alexander did after wishing everyone a good evening was remind the crowd that his affection for Ms Sylvia is so deep that he used to call her Mom. He was seven when he started walking hots at Douglas Park, and it was Ms Sylvia’s brother-in-law who helped give him his start as a jockey.

“Jake used to tell me all the time, ‘What you should do is try and get your jock’s license,’ ” he said. “Back then, it was all just black and white, no other nationalities, and there weren’t any black jockeys riding. I said, ‘Man, you want to make me the guinea pig?’ and he said, ‘Someone has to be!’

“I was still in junior high school, and I was a boxer at Columbia Gym when Muhammad Ali was boxing. When I did that, they asked if I was going to be a boxer or a jockey. I said, ‘I would rather be a jockey because those gloves hurt.’ Jake put me on my first horse and bought me my first jock’s saddle. I still have it at home now, but it’s so old all the leather is peeling.”

Alexander became a jockey at 17, and he still remembers how he surprised many with is talent before his career was interrupted by Vietnam.

“They said I couldn’t do it, and I said I could,” he said. “The biggest race I ever rode was a $175,000 race, and I was 98/1. I won the race, and it paid $210. From there, they were coming to me asking me to ride this one, ride that one. At the time it wasn’t, like, real, the money, because I was just 17. I was on my way to Vietnam and didn’t know it.

“They were drafting young kids out of school to go to war, and I said, ‘I ain’t gonna get drafted,’ so I went and joined the Marine Corps. Glory be to God, I went in there and came out a staff sergeant and was honorably discharged. I was a tunnel rat. I was underground for eight months, two weeks and 26 days. When we left Standiford Field [the Louisville airport] there 75 of us, and only 25 of us came back. After that, I went back to riding. It just came natural to me.”

Alexander retired around the same time as a Churchill legend, and, while he told his story about it with good humor and a smile, it also brought up the ever-powerful question of what-if.

“I retired with Pat Day,” he said. “When they gave him the statue in the paddock, they gave me a season pass. I said why didn’t you put a statue of me on the other side? They said, ‘Well, uh, Mr Alexander, the reason we didn’t is because you didn’t win any Derbys.’ I said, ‘The only reason I didn’t get to win ’em is because you wouldn’t put me on ‘em.’ ”

An important history

The aim of Better Lucky Than Good was to take an in-depth look into the lives of people from all types of backgrounds who were rarely asked their story. Stories beget more stories, and nights like the one at Syl’s Lounge helped open the floodgates, as the mic was passed around to men and women who grew up with Churchill in their blood.

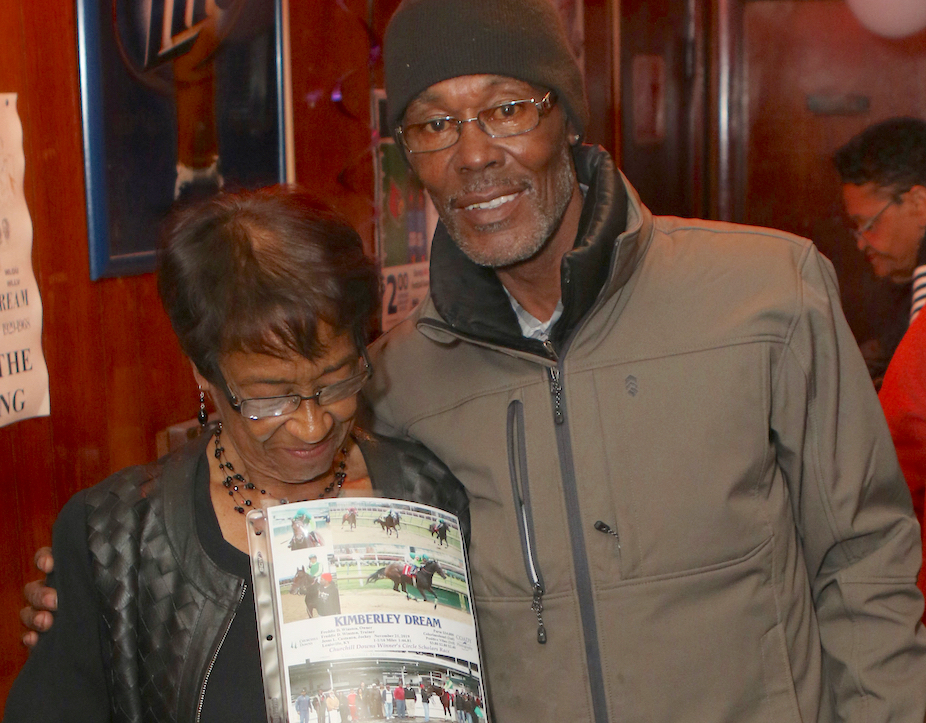

For instance, Freddie Winston, the son of legendary groom Scotland Yard, was in attendance and shared his own memories of the past and the very present. Earlier that day, Winston, who has retired from driving for the Transit Authority of River City, saddled his own horse, Kimberley Dream, to her third victory during the fall meet at Churchill.

As the freshly printed winner’s circle photo was passed around and admired, Ms Sylvia held court, the unquestionably respected queen of her domain. Her stories about being a black racehorse owner in 1970s America? Unquestionably moving.

“The whole thing was truly unbelievable,” she said. “To be in the paddock with a horse you were going to run in a race was unheard of. We were poor people. We didn’t have anything, but we had the nerve. And it worked pretty good.”

From the archive: Great racehorses who transcended the sport – the top five

From the archive: Frank Frankie – Dettori on his highs, his heroes, and his heartaches

View the latest TRC Global Rankings for horses / jockeys / trainers / sires