In the latest instalment of his popular series looking at racing-based films, our correspondent on the celluloid revisits a gritty 1950s classic of the genre featuring William Holden as a down-at-heel jockey agent

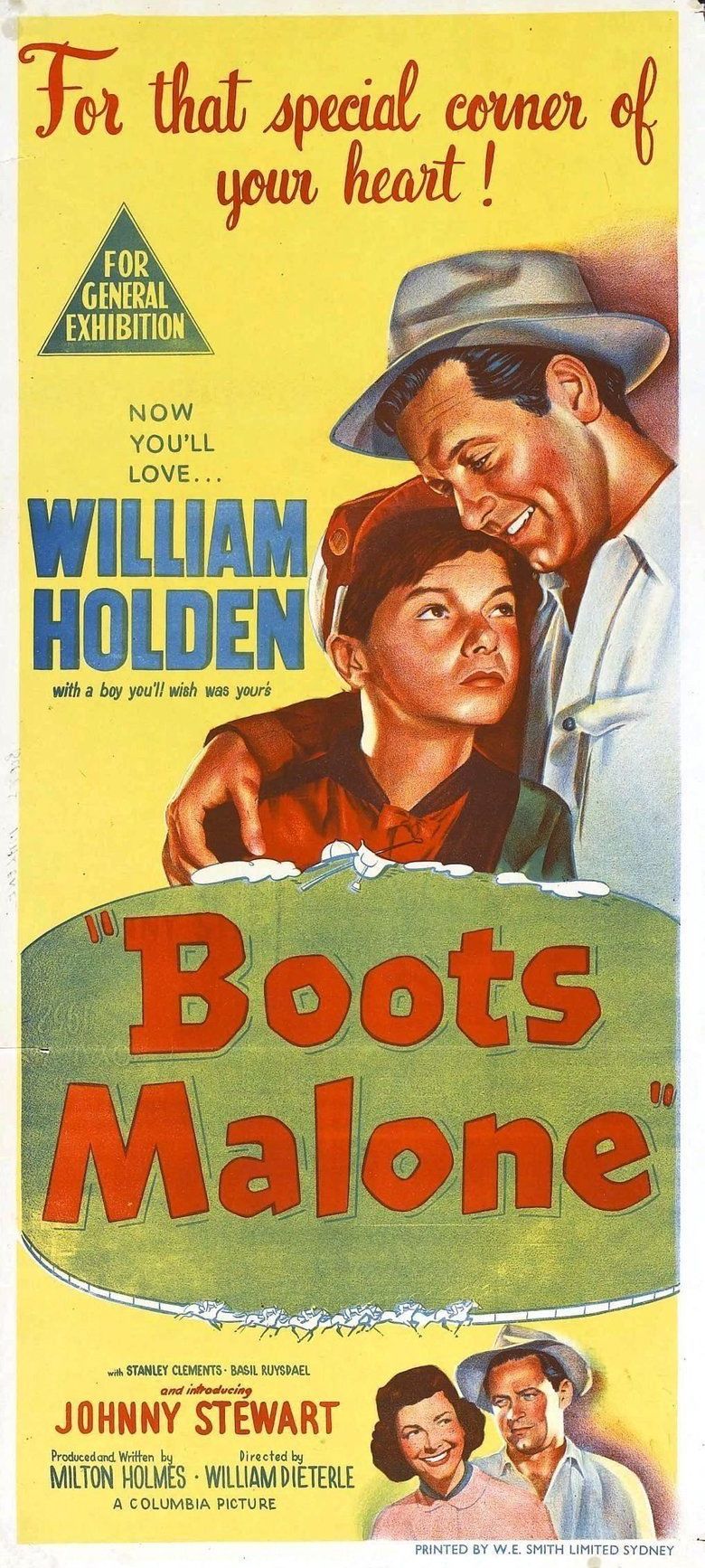

Boots Malone (1952)

Boots Malone (1952)

directed by William Dieterle; starring William Holden, Johnny Stewart

In the decade following the end of World War II, there were at least three dozen horse racing movies released into theatres by Hollywood studios. They include flimsy biopics of Seabiscuit and Dan Patch, a B-grade Bing Crosby musical, comedy vehicles for both Martin & Lewis and Abbott & Costello, and a collection of racetrack fairy tales that assumed the audience knew just enough about the sport to be in on the joke.

Then there is Boots Malone.

Malone is a jockey agent played by William Holden. Early on, we find Boots bunking in a backstretch tack room on ‘poverty row’ thanks to the generosity of an old trainer who goes by Preacher Cole. It’s been a year since Malone’s meal ticket, top jock Earl West, was killed on the clubhouse turn at Dellington Park. Since then, Malone has been on the skids, waiting for another Earl West to come along. Preacher wonders aloud if Malone has had any likely prospects.

Drunks, cripples, boneheads, has-beens

“Sure, plenty of boys,” Malone says. “They’re coming at me in my sleep. Jocks half-blind, jocks with kidney trouble who’d get dizzy on a rocking horse, jocks with steel collarbones who couldn’t whip a rug. Drunks, cripples, boneheads, has-beens. There isn’t even an apprentice boy around that knows which end of a horse to feed.”

Then one shows up, out of the blue, a rich runaway played by young Johnny Stewart, new to movies but known on Broadway, where he was in the original cast of The King and I. What follows is a series of interlocking plot turns that wind seamlessly to a satisfying end that  honors the arc of Malone’s journey from cynical hustler to possible redemption, even though he is on the lam.

honors the arc of Malone’s journey from cynical hustler to possible redemption, even though he is on the lam.

Familiar cast list

The cast is peppered with familiar faces. The ex-jock played by Stanley Clements, all grown up from his days with the East Side Kids, is Malone’s running mate. Harry Morgan – later of Dragnet and MASH – is groom Quarterhorse Henry.

Ed Begley, a heavy’s heavy, is the heartless racehorse owner Howard Whitehead. You know the auto mechanic is Hank Worden, from John Ford westerns, the moment his elastic, down home baritone tells Boots and the gang it’ll cost a hundred and fifty, “cash on the barrelhead,” to fix their broken-down truck.

There’s even a glimpse of Whit Bissell, an actor with more than 300 screen credits, without whom it seemed no movie or TV show could be made.

Boots Malone was released in January 1952. Then, as now, movies released in the first month of the year were not considered serious merchandise. Over the following months, a cavalcade of blockbusters were rolled out, including The Greatest Show on Earth, Singin’ in the Rain, and High Noon. What chance did a little horse racing movie have?

None, as it turned out. But that’s not how Milton Holmes saw it. Holmes was both the producer of Boots Malone and the man who wrote the screenplay. And what a screenplay it is, brimming with allusions to real-life racing situations that suggested someone spent a lot of time hanging around the dustier corners of the backstretch.

Rightfully proud

Holmes was rightfully proud of the film director William Dieterle delivered to the screen. But when Columbia Studio dragged its feet in promoting the movie, Holmes sued.

Dieterle had fled his native Germany to escape the rise of Hitler and thrived in Hollywood as the director of prestige films like A Midsummer Night’s Dream and The Life of Emile Zola, which won the Oscar for Best Picture in 1937.

After the war, Dieterle turned to tighter, more modern themes, like the film noir Dark City and the political adventure The Peking Express. When Holmes’s script for Boots Malone hit Dieterle’s desk, the last thing the director was going to make was a version of the cliché-ridden Salty O’Rourke, for which Holmes had received an Oscar nomination in 1945.

There are a handful of obligatory softball scenes between the agent and the young jockey. But for the most part Dieterle kept up an edgy verisimilitude that differed from the pile of lame racetrack flicks.

The vernacular is very much of the era, from “the shrimp’s got a clock in his head” to “that horse is cut up more ways than a boarding house pie.” Any exposition is quick and part of the drama, as when Preacher explains the claiming game to the questioning kid, or when another veteran trainer pushes back on the owner who wants to violate an unwritten rule: “There’s an understanding around the track,” the trainer says. “A man with one horse, you don’t claim it. You don’t put him out of business.”

The vernacular is very much of the era, from “the shrimp’s got a clock in his head” to “that horse is cut up more ways than a boarding house pie.” Any exposition is quick and part of the drama, as when Preacher explains the claiming game to the questioning kid, or when another veteran trainer pushes back on the owner who wants to violate an unwritten rule: “There’s an understanding around the track,” the trainer says. “A man with one horse, you don’t claim it. You don’t put him out of business.”

Of course, the guy claims the horse anyway, which triggers a thread of the story that suggests resurrection of fortunes for Malone through his young protégé. Themes of lost love and parenthood hover in the background but never overwhelm the characters  and their immediate destinies. Nothing is ever as simple as movies of the genre pretend.

and their immediate destinies. Nothing is ever as simple as movies of the genre pretend.

Boots Malone was a bit of a sidestep for Holden, who at the time was just coming into his own as an A-list movie star after a decade of lightweight roles. In 1950, Holden scored big with Born Yesterday and Sunset Boulevard. His other release in 1952 was Turning Point, also with Dieterle, a riveting big city political drama. Then came his Oscar-winning Stalag 17 in 1953, and Holden was never anything but a leading man again.

Dieterle and Holmes, however, did not fare as well. An avowed anti-fascist, Dieterle was suspected of left-leaning politics during America’s Red Scare and, in his words, was “gray-listed” out of work commensurate with his resumé. He eventually returned to Germany, which is ironic in a sad condemnation of the turn taken by US politics in the 1950s.

Holmes suffered a similar fate. Suing the studio labeled him as a troublemaker who was not worth the hire. After Boots Malone, he turned to writing for television, ultimately lending his name to the popular series Mr. Lucky, which was based on his 1943 story and screenplay for the Cary Grant movie of the same name.

At least Holmes went out on a high note. Bosley Crowther, the notoriously straight-laced film critic for the New York Times, showered Boots Malone with surprising praise.

Peculiar tribe

“A peculiar tribe that has often been studied on the screen – the down-at-heel, cavalier characters that hang around race-track barns – is given another inspection in Columbia’s Boots Malone and is found a good bit more entertaining than it has been in some previous race-track films,” wrote Crowther.

“As a matter of fact, the rough assortment of horse trainers, jockeys, agents, touts and granite-faced track employes that appears on the Paramount’s screen forms a sharp and amusing caboodle we’d like to encourage you to meet.”

What Crowther appreciated, without knowing why, were the numerous touches to Boots Malone that suggested there were racetrackers crawling all over the movie set.

Here’s Stewart settling atop a horse before a workout, automatically looping his reins in a jockey’s knot without so much as a g lance. Here’s Holden on a pony in a western saddle, riding alongside Stewart on a racehorse and shouting instructions as they gallop at a full clip. Here’s Stash as the kid wins his first race by a pole, shouting: “Sit back and curl your moustache. You’re home free!”

lance. Here’s Holden on a pony in a western saddle, riding alongside Stewart on a racehorse and shouting instructions as they gallop at a full clip. Here’s Stash as the kid wins his first race by a pole, shouting: “Sit back and curl your moustache. You’re home free!”

There is a drunk in a tux bidding up a horse at an auction, a private detective on the trail of the kid, and a big-time bookie who does his own dirty work. The shady side of the game is played as background atmosphere, although there is a race at a bush track in which the horse of high hopes is stiffed. He was shod with heavy shoes.

“Of course, it may be that the people who are soberly and properly concerned with having it known that horse-racing is as honest as the day is long – at least around the big tracks – may take some exception to this film,” Crowther concluded. “But the plain old moviegoer or the fellow who hangs on the rail should be happy to have his money going on this charging Boots Malone.”

• View all Jay Hovdey’s features in his Favorite Racehorses series

Horse racing at the movies: The Black Stallion is a bonafide classic among the greatest horse fables

Horse racing at the movies: Casey’s Shadow gets into the details like few feature films

Horse racing at the movies: Champions was different from the maudlin crowd

Azeri: ‘She was easy to adore … she was all racehorse’ – spotlight on a forgotten filly

View the latest TRC Global Rankings for horses / jockeys / trainers / sires