Steve Dennis begins a new series ahead of this year’s 245th edition of the Derby at Epsom on Saturday June 1

Heads or tails?

This is the story of the Derby, the original Derby, the Derby, the one that over time created the landscape of horse racing in its own image, its own name. As an exercise in branding it is without parallel in the sporting world and arguably the real world beyond that, a marketing-man’s fever-dream of global domination and instant recognition.

And before we move on by looking back, it is called the ‘Derby’ and not the ‘Epsom Derby’ because it is the original, the common ancestor, and no other identification or qualification is required.

Rhymes with ‘Barbie’

For the benefit of our American chums, it rhymes with ‘Barbie’ – though admittedly, our transatlantic cousins usually feel the need to add the qualifying prefix ‘Epsom’ to differentiate from their own ‘Durrby’ variant.

So the question comes again. Heads or tails? It is racing mythology now, and as such may never have happened at all, or happened in a different, less satisfying manner, but the story goes that the Derby was born from the toss of a coin.

In 1779, at a party thrown near Epsom by Edward Smith-Stanley, the 12th Earl of Derby, to celebrate victory in the inaugural running of the Oaks with his filly Bridget, the conversation turned to plans to stage a similar race for colts. And this race needed a name.

In 1779, at a party thrown near Epsom by Edward Smith-Stanley, the 12th Earl of Derby, to celebrate victory in the inaugural running of the Oaks with his filly Bridget, the conversation turned to plans to stage a similar race for colts. And this race needed a name.

Should it be called after the party’s host Lord Derby? Or perhaps after his pal Sir Charles Bunbury, the senior steward of the Jockey Club? The social mores of the era dictated that Bunbury should defer to the senior peer, and that is probably what happened.

Irresistible legend

However, irresistible legend has it that a party guest fumbled through his pockets for a coin – unlikely to have been a penny, given the social standing of the revellers, more likely a gold sovereign – and uttered the time-honoured command. There is no record of whether the coin landed showing the head or the tail, but in this version of events Lord Derby called correctly and the new race was named in his honour.

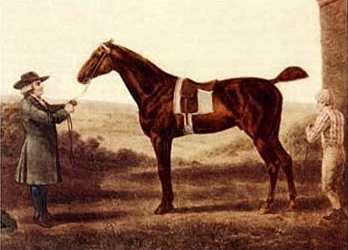

The first edition of the Derby was run over a mile at Epsom in May 1780 and won by Diomed, owned – neatly – by Bunbury himself. All the rest is racing history, and also its vivid, vibrant present.

The Derby is the most important, most famous Flat race in the world, not because of its great history, its popularity or the brilliance of its winners – although all three factors are substantive – but because it is the father of all the Derbys around the world, a sireline that runs from the surf of Del Mar to the tower blocks of Hong Kong via almost every stop on the racing road in between.

The Derby is the most important, most famous Flat race in the world, not because of its great history, its popularity or the brilliance of its winners – although all three factors are substantive – but because it is the father of all the Derbys around the world, a sireline that runs from the surf of Del Mar to the tower blocks of Hong Kong via almost every stop on the racing road in between.

In practically every jurisdiction the most prestigious race restricted to three-year-olds is suffixed as a Derby, a relic of both empire glory and the desire to manufacture instant gravitas and tradition.

The Irish Derby at the Curragh (first run in 1866), the Derby Italiano at the Capannelle (1884), the Victoria Derby at Flemington (1855), the South African Derby at Turffontein (1907), the Indian Derby at Mahalaxmi (1943) and many more, although the French typically like to do things slightly differently with their Prix du Jockey Club, and Canada’s big race for three-year-olds is the King’s Plate, albeit there is also a G3 contest called the Canadian Der by.

by.

The Kentucky Derby, America’s greatest race, came into existence in 1875 as a deliberate carbon copy of the Derby, a chip off the old block.

Louisville socialite Colonel Meriwether Lewis Clark travelled to Europe to glean ideas for the revitalisation of the sport in the bluegrass state following the devastation of the Civil War, attended the Derby – by then extended to its traditional distance of a mile and a half – and brought it back home wholesale.

“Today will be historic to Kentucky annals,” ran the raceday editorial in the local Louisville Courier-Journal. “It is the first ‘Derby Day’ because the president [Clark] hopes to make this a duplicate for the great English turf event.”

Duplication and veneration

Duplication and veneration

Duplication, veneration. The potency of the Derby brand even works retrospectively – the Kiplingcotes Derby, an arcane and enthralling amateurs’ race run across four miles of open country in the East Riding of Yorkshire since 1519, was initially christened the Kiplingcotes Plate.

At some point post-1780, whether through design or vernacular acceptance, it became known as the Kiplingcotes Derby, the word ‘Derby’ having become shorthand for any race considered especially important.

And, of course, not just any horse race. The Derby name has made the quantum leap beyond the confines of racing into the wider realm of sport and, by extension, into any situation that involves competition.

In Britain, the biggest event in dog racing is the Greyhound Derby (first run 1927). When the petrolheads get together to smash up their cars they call it a Demolition Derby, and when younger would-be petrolheads compete for a prize they call it a Soapbox Derby. Those getting their skates on have their Roller Derby, while even the beasts of burden giving rides to children on their seaside summer holidays have their Donkey Derby.

Then there is the concept of a local derby, a derby game – Liverpool vs Everton, Yankees vs Mets, Queensland Reds vs NSW Waratahs – that likely also derives from the Earl of Derby’s Derby, although as with the mythology surrounding the coin-toss it depends what you choose to believe.

Then there is the concept of a local derby, a derby game – Liverpool vs Everton, Yankees vs Mets, Queensland Reds vs NSW Waratahs – that likely also derives from the Earl of Derby’s Derby, although as with the mythology surrounding the coin-toss it depends what you choose to believe.

Keen rivalry

A schism has evolved between those who prefer the explanation descending from the anarchic semi-war ‘contests’ of primitive Shrovetide football between the inhabitants of Ashbourne village in Derbyshire in the 12th century, and those siding with the gradual and pervasive usage of the word ‘derby’ in the 19th century, plainly taken from the increasingly popular Epsom feature, to come to mean any notable sporting event with a keen rivalry attached: a derby game.

Each has claims, although the Derby adherents have consistent recency on their side, as well as the entry in the Oxford English Dictionary that includes mention of the horse race but not the medieval football game. Perhaps in this particular derby game we’ll call it 1-0 to the race.

It is amusing to consider that had the coin-toss gone the other way we might be talking of the Kentucky Bunbury, a Soapbox Bunbury, a bunbury fixture between Arsenal and Tottenham Hotspur, and the Bunbury Italiano. Perhaps it’s for the best, at least linguistically, that Lord Derby chose correctly.

It is amusing to consider that had the coin-toss gone the other way we might be talking of the Kentucky Bunbury, a Soapbox Bunbury, a bunbury fixture between Arsenal and Tottenham Hotspur, and the Bunbury Italiano. Perhaps it’s for the best, at least linguistically, that Lord Derby chose correctly.

The original race that bears his name still thrives, although not as thickly as in its prolonged heyday that stretched more than 150 years from the beginning of the Victorian era to the 1980s.

In 1829, The Times thundered that – inaccurately, presumably – “the whole world was at Epsom on Derby day”, although when waiting to be served at the bar at a busy racecourse it can indeed seem a little like that. A decade later, Charles Dickens reckoned that the population of Epsom’s green acres on Derby day “may be counted in the millions”.

Old-school newsreel footage

In 1973, the BBC estimated that a million people were on the grounds for the great race, but failed to mention how few of them backed the 25-1 winner Morston. The vast majority would have been on the Hill, the infield, free-to-enter public land that in old-school newsreel footage was so densely, darkly packed with humanity that barely a blade of grass is visible.

These days there’s plenty of grass to be seen there, as the British public have found other things to do with their leisure hours. Yet the Derby still stands firm, like an old oak tree in a rolling green meadow, its branches blown and bent by the would-be winds of change but gamely intact, still blooming grandly in the warmth of early summer, still connecting the past with the future, still the greybeard daddy of all Derbys and derbies everywhere.

In a society moving inexorably towards a cashless future, the old ritual of tossing a coin to determine an outcome grows increasingly archaic. If the Derby were being inaugurated today, the Earl of Derby and the senior steward of the Jockey Club might have a slightly incongruous, vaguely undignified bout of rock-paper-scissors to reach agreement on its name.

Well, they did things properly back in 1779. The coin would have caught the light as it fizzed up, spun down, landed flat in the palm of someone’s hand. Heads, tails, whichever way it fell, it gave the world a Derby, gave the world a word.

• Visit the Betfred Derby Festival website

View the latest TRC Global Rankings for horses / jockeys / trainers / sires