As he continues his unmissable series, Steve Dennis considers the patchy recent record of Epsom heroes kept in training at the age of four and beyond

A more liberated assessment suggests instead that it might be considered the end of the beginning, the end of the phoney war of the two-year-old season and the spring trials, after which the glorious winner moves on to pursue yet more glory through the rest of his three-year-old campaign.

But it might also be considered the beginning of the end, as there is little a Derby winner can do after beating his peers at Epsom that will enhance his record, his standing, his resonance in the racing world – victory in the Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe or at the Breeders’ Cup the only plausible alternatives for extra merit.

The temptation – unspoken, of course, except for that frantic period in the mid-1980s, when bloodstock values ballooned and everyone was not just talking about it but doing it with unseemly haste – is to cash in the chips, monetise the asset, get those golden hooves off to stud quicksmart before they become feet of clay.

The temptation – unspoken, of course, except for that frantic period in the mid-1980s, when bloodstock values ballooned and everyone was not just talking about it but doing it with unseemly haste – is to cash in the chips, monetise the asset, get those golden hooves off to stud quicksmart before they become feet of clay.

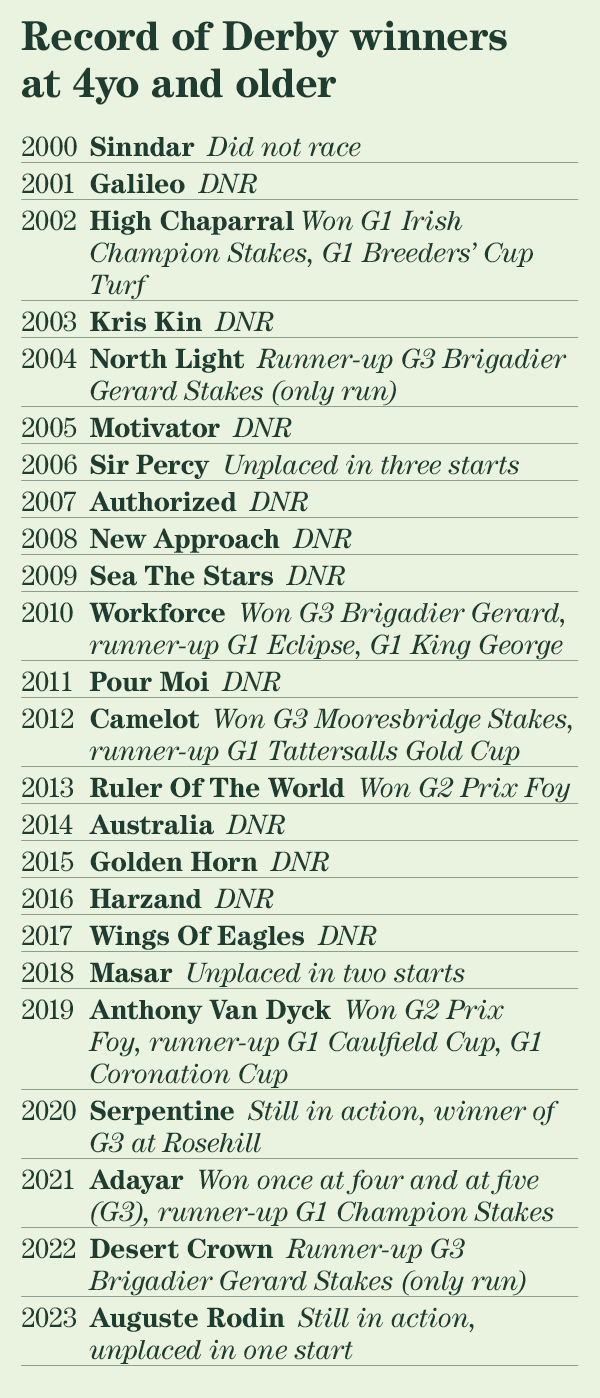

Because that’s what happens. For all the validity of keeping a Derby winner on the track at four being great for racing, providing the public with the opportunity to maintain the important bond between star and star-struck, it tends to be not great at all for the horse in question (as the accompanying table illustrates).

Hostage to fortune

All the recent precedents indicate that prolonging a Derby winner’s career beyond another winter leaves him vulnerable as a hostage to fortune.

Since 2000, half of the 24 Derby winners have been kept in training at four, and only one of that doughty dozen was able to carry over his sophomore stardust into further G1 success – the mighty High Chaparral, who signed for two more victories at the highest level as a four-year-old, including that memorable dead-heat in the Breeders’ Cup Turf at Santa Anita.

There have been a couple of near-misses, notably Workforce, beaten by a half-length in the G1 Eclipse at Sandown in 2011, and ill-fated Anthony Van Dyck, who came up a head short in the Caulfield Cup in 2020 on the Melbourne circuit. There is also no knowing what the very lightly raced Desert Crown might have achieved but for a fatal gallops injury halfway through 2023.

Injury also compromised the career of Masar, Godolphin’s first Derby winner, who sustained a soft-tissue leg injury before his next target and missed the rest of his three-year-old season. He recovered and was an obvious candidate to race on, a shot to nothing given his owner’s vast wealth of alternatives both on the track and in the stallion barn.

“His Highness Sheikh Mohammed was keen to see him stay in training, so in order to give him the best chance next year we decided to give him the rest of this season off,” trainer Charlie Appleby told The Guardian in July 2018. “There is a chance there’s more to come.”

Unfortunately there wasn’t, and Masar ran well below his best in two starts at G2 level before being retired halfway through the year. Soundness is an obvious stumbling block for any Thoroughbred, let alone a Derby winner, who – aside from the likelihood of a lower-grade reappearance – has to maintain a career in the biggest, most competitive, most draining races.

Another layer of difficulty

He must also concede weight to the best three-year-olds around and do battle with later-maturing members of his own age group; little wonder so few of those who have tried have succeeded. There is also increased pressure, given the bloodstock industry’s unrelenting and misguided obsession with speed, for a Derby winner to score at ten furlongs in order to be a truly attractive prospect at stud, something that simply provides another layer of difficulty to overcome.

Masar’s stablemate Adayar almost picked up that golden ticket, making a belated reappearance at four and beaten just a half-length in the ten-furlong Champion Stakes at Ascot. It was a performance that encouraged connections to defer retirement a second time in order to punch that ticket, tick that box.

“To start with he will be campaigned over a mile and a quarter because of his stallion CV,” Appleby told this website last April, as Adayar neared a return to action at five.

“In this day and age, they want to see a bit more speed on the page. What he achieved in his three-year-old career, winning the Derby and King George, was fantastic and everyone was delighted. From a commercial point of view everyone would like to see that mile and a quarter stamped.”

Adayar stamped it all right, but only at G3 level, and two subsequent defeats brought the project to an early end. He was remarkably rare in being a Derby winner still competing at the age of five, but by far the most extreme example of the genre is Serpentine, shock Epsom hero of the Asterisk Year of 2020, who is seven and still gamely continuing what is surely the most extraordinary post-Derby career on record.

As a four-year-old Serpentine was sent for the Gold Cup at Royal Ascot over 2½ miles, becoming the first Derby winner to follow that once-common path for more than 50 years. He finished eighth and was later sold to Australian mega-owner Lloyd Williams, the Coolmore empire having sufficient sons of Galileo on the ranch to not mind letting one get away.

Veterinary reasons

That was unusual, but not unknown. Unprecedented, though, was the decision to have Serpentine gelded for what Williams’ son Nick described as “veterinary reasons”, adding: “A Derby winner, your first preference would be to leave him a colt, but it will certainly improve him as a racehorse being a gelding, so we did that.”

Serpentine has certainly escaped the fate of the previous Derby winner to be gelded, the unmanageable Prince Leopold (1816) who died shortly after the operation, and it is finally becoming easier to go along with the notion that the snip has improved him as a racehorse.

He is just three-for-17 in Australia, although he has shown distinctly upgraded form in 2024, winning a stakes race at Randwick and following up in the G3 James Squire Neville Sellwood Stakes at Rosehill, then finishing a close-up fourth in the two-mile G1 Sydney Cup back at Randwick.

As a gelding, his career is now open-ended; he has become the Voyager 1 of Derby winners, every day that passes propelling him further into uncharted territory.

Serpentine’s example might have deterred the Coolmore ‘lads’ from extending the racing life of 2023 Derby winner Auguste Rodin, whose mercurial career has been bizarrely binary in nature – the colt’s form figures following a second-place on his debut are 1110110110. However, when the decision to keep the son of Deep Impact – also successful in the Irish Champion Stakes and Breeders’ Cup Turf – in training was announced, unbridled optimism was the order of the day.

Apparent hex

“We’re delighted,” said trainer Aidan O’Brien. “He looks like a horse who could be even more exciting next year so we’re all looking forward to it. It’s brilliant for us all, for everyone who follows racing.”

Unfortunately, Auguste Rodin, as per his strange numerical pattern, produced a lifeless display when trailing home last in the Dubai Sheema Classic at Meydan in March, lending further weight to the apparent hex hanging over Derby winners at four.

However, given his exceptional pedigree there is absolutely no danger of Auguste Rodin warily following Serpentine into the veterinary surgery, and his next target is reportedly either the G1 Tattersalls Gold Cup at the Curragh on May 26, certainly among the softer options available at the highest level (although, in another demonstration of the Derby hex, his predecessor Camelot was beaten in the race at 4-11 in a four-runner field in 2013).

Win there and the 21-year curse is lifted, and the summer opens up with a cornucopia of top-level possibilities at ten furlongs and a mile and a half, with the prospect of mirroring the achievements of High Chaparral on the international stage.

But lose again, and Auguste Rodin may soon become another member of the club who might have been better served by the mantra ‘quit while you’re ahead’.

• Visit the Betfred Derby Festival website

‘Epsom is not where the Jockey Club would like it to be’ – interview with general manager Tom Sammes

A life after racing: Aussie star Cascadian joins Godolphin Lifetime Care program

Tadhg O’Shea: I thought I was Mick Kinane, Lester Piggott and Frankie Dettori rolled into one

View the latest TRC Global Rankings for horses / jockeys / trainers / sires