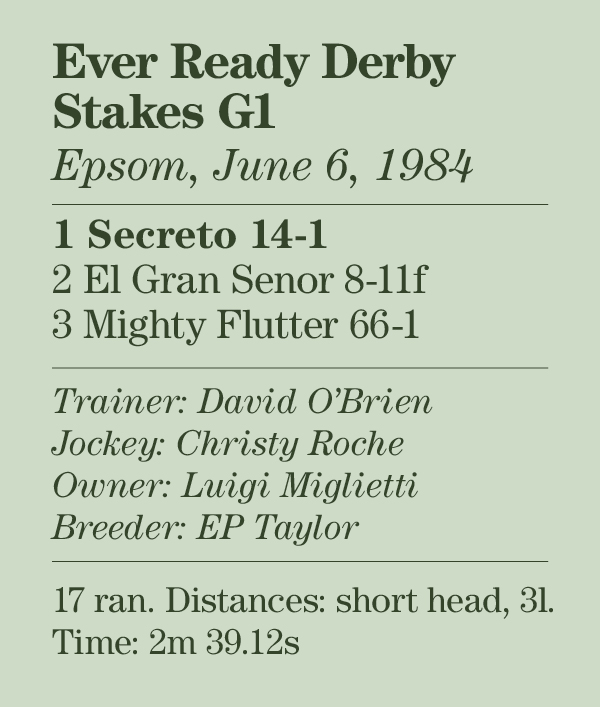

Our Epsom series continues with a 40th anniversary feature as Christy Roche recalls one of the most thrilling Derbys in living memory – and one of its biggest shocks

The 1984 Derby was considered a clear-cut affair, all over before it even began.

The 1984 Derby was considered a clear-cut affair, all over before it even began.

Everyone was confident it would be won by a son of Northern Dancer trained by a man named O’Brien, ridden by a tough-cookie Irish jockey, with the manner of victory inevitably something to marvel at, something to echo down the ages.

And so it came to pass; yet this tale of the expected would have the most outrageous twist.

The abiding image of the race is the hot favourite El Gran Senor cruising into the lead on the bridle two furlongs out, a vision of barely restrained power and class, while the hard-ridden Secreto fought gamely to keep him in range.

The intensity and drama of their duel was enhanced by the situation off the track, with a great racing family divided in competition and unprecedented amounts of money and prestige at stake. This truly was a race that had everything.

Beforehand the focus was fixed upon El Gran Senor, champion two-year-old colt and unbeaten in six starts including the 2,000 Guineas, won with a raking panache from probably the best field ever assembled for the historic one-mile Classic at Newmarket.

El Gran Senor – named with the nickname of his sire Northern Dancer’s trainer Horatio Luro – was trained at Ballydoyle by the incomparable Vincent O’Brien, already winner of six Derbys; ridden by the great multiple champion Pat Eddery, winner of two Derbys; owned by bloodstock titan Robert Sangster, whose famous green-and-blue silks had been carried by two Derby winners in the preceding seven years.

Hottest favourite for 37 years

He indisputably had the right stuff and the betting public bought in with both hands, making him the hottest Derby favourite for 37 years at odds of 8-11.

They were not the only ones putting their money down. In the days leading up to the race – as outlined in Horsetrader, a rip-roaring account of Sangster’s equine empire – El Gran Senor had been valued at $80 million by a group of major bloodstock players who would purchase 50 per cent of the colt, if he won the Derby.

If? Such a little word, always a huge significance. And there were just a few sceptics using that word about El Gran Senor, who had never gone beyond a mile, wondering aloud if he was too fast, too brilliant to truly stay the searching mile and a half at Epsom.

Among the 16 rivals opposing this modern Achilles was a familiar face. Secreto was also by Northern Dancer – out of a Secretariat mare, hence his name – and the two foals had reportedly shared the same paddocks at Windfields Farm in Maryland before the sales ring separated them. But the twisting, twining strands of fate were not untied.

Secreto, purchased by Venezuelan tycoon Luigi Miglietti, was trained by Vincent’s son David O’Brien at his yard on the far side of the Ballydoyle gallops from his father, where two years earlier he had sent out Assert to win the Prix du Jockey-Club and Irish Derby in those all-conquering Sangster colours. The intricate, intrinsic bonds between the horses, the people, were woven together as densely as any soap-opera plot.

Secreto, purchased by Venezuelan tycoon Luigi Miglietti, was trained by Vincent’s son David O’Brien at his yard on the far side of the Ballydoyle gallops from his father, where two years earlier he had sent out Assert to win the Prix du Jockey-Club and Irish Derby in those all-conquering Sangster colours. The intricate, intrinsic bonds between the horses, the people, were woven together as densely as any soap-opera plot.

Honour guard

On his previous start Secreto had been favoured to win the Irish 2,000 Guineas but was narrowly beaten into third behind sire sensation-to-be Sadler’s Wells, and despite his odds of 14-1 in this first sponsored Derby – endowed by battery giant Ever Ready – his jockey Christy Roche was optimistic that they were not there merely to serve as an honour guard for El Gran Senor.

“After the Irish Guineas, we thought the step up to a mile and a half would improve Secreto plenty,” says Roche, now an energetic 74, caught up in the moment as surely as he had been 40 years ago.

“I fancied our chances, even going up against El Gran Senor. I was walking the track at Epsom and met John Magnier [Coolmore supremo then and now] along the way, and told him I thought my horse would beat the favourite.

“He laughed, and told me he’d had a saver bet on Secreto to win a million old Irish punts, it must have been. He said that would stop him if nothing else did.”

The 250-1 shots Cataldi and At Talaq, a future winner of the Melbourne Cup, set a relatively benign pace as El Gran Senor settled comfortably behind the first half-dozen. Secreto was on his heels, as close now as he had been in those Windfields paddocks years before. “I wanted to follow Pat,” says Roche. “I had my eyes on Pat all the time.”

He and everyone else at Epsom, everyone everywhere. El Gran Senor coasted down the hill and around Tattenham Corner as though on wheels, poetry in motion. The three-furlong pole comes fairly quickly after the turn, and as the front-runners began to empty out Roche started to push and shove aboard Secreto, but Eddery was sitting as still as a birdwatcher.

Absolutely cruising

“Look at El Gran Senor, he’s absolutely cruising!” called commentator Graham Goode, and everyone looked, and seeing was disbelieving. El Gran Senor was cantering, as though he had just stepped into the race, while all around his Derby rivals were at their limit. He eased languidly into the lead at the two-furlong pole, pursued by a hard-pressed Secreto.

“He was a tough little horse and he was responding really well,” says Roche. “But Pat was cruising. It looked like El Gran Senor couldn’t be beat, but the one thing in my head was the possibility that he wouldn’t stay the mile and a half. That’s what kept me going.”

Inside the final quarter-mile, Eddery turned his head to the right and looked lingeringly, almost condescendingly at the busy Roche, measuring his superiority, making a point. Yet now Secreto had drawn almost alongside the favourite.

“Pat didn’t say anything to me, but the way he looked at me gave me further encouragement,” says Roche. “I took it as a distress signal from Pat.”

Indeed, within just a few strides Eddery began working at El Gran Senor, nudging, niggling, and as they passed the furlong pole he reached back and – unthinkable – cracked the Senor’s backside with his whip.

That regained him a short lead, but Secreto kept coming, and now panic had replaced confidence in Eddery’s every movement. The final furlong was as tense, as intense as a horse race can get.

“When we got to El Gran Senor’s girth my horse kept battling for me,” says Roche. “Pat knew he was in trouble. I gave Secreto a hard ride – the stewards would probably sign me off for a year these days – but he responded all the way home. At the line, I knew we’d won.”

“When we got to El Gran Senor’s girth my horse kept battling for me,” says Roche. “Pat knew he was in trouble. I gave Secreto a hard ride – the stewards would probably sign me off for a year these days – but he responded all the way home. At the line, I knew we’d won.”

The $40m short-head

Thirty yards out, Secreto drew level with El Gran Senor, both jockeys asking for everything and getting it. Then Secreto put his nose in front and kept it there long enough to win the Derby. The press called it the $40 million short-head, the amount by which El Gran Senor’s value diminished in defeat.

Immediately, the despairing, disconsolate Eddery lodged an objection to the winner for leaning on him in the closing stages. It was a desperate, last-chance roll of the dice, and Roche was unafraid.

“Pat knew it wouldn’t make a difference, but he was trying everything he could,” he explains. “We were in the stewards’ room, and as soon as they showed the film we could see that Pat’s horse came to me rather than the other way around. His face fell; he knew. And I didn’t have to say anything.

“Pat knew it wouldn’t make a difference, but he was trying everything he could,” he explains. “We were in the stewards’ room, and as soon as they showed the film we could see that Pat’s horse came to me rather than the other way around. His face fell; he knew. And I didn’t have to say anything.

“Pat took a great deal of criticism after the race, wrongly, in my opinion. He was travelling so easily and found himself in front too soon, much earlier than he’d have wanted to be.”

‘I’m sorry’

Elsewhere, the O’Brien family was coming to terms with the enormity of what had just happened. The son had bested his father in the greatest arena of all in the most sensational manner, had denied him the ultimate prize while claiming his own crowning glory. David O’Brien’s first words to his mother Jacqueline were: “I’m sorry.”

“For goodness’ sake, don’t say that,” she answered, as any mother would. “Dad and I are both just thrilled.”

Paternal pride vied with professional disappointment in Vincent O’Brien’s heart, and pride won hands down. “I’m absolutely thrilled for my son,” he said. “I’m so glad the objection went the way it did. I’d never have got over it if the race had been taken from my son.”

Secreto never ran again, a minor injury preventing him from meeting his next engagement and a major stud valuation preventing connections from persevering thereafter. He was not a success as a stallion.

El Gran Senor ran once more, proving his stamina beyond doubt by winning the Irish Derby at the Curragh. Fertility problems dogged his stallion career, although he sired the top-class Rodrigo De Triano and Breeders’ Cup Sprint winner Lit De Justice.

El Gran Senor ran once more, proving his stamina beyond doubt by winning the Irish Derby at the Curragh. Fertility problems dogged his stallion career, although he sired the top-class Rodrigo De Triano and Breeders’ Cup Sprint winner Lit De Justice.

Vincent O’Brien died in June 2009, his position as the world’s greatest trainer unassailable. Pat Eddery, Robert Sangster and Luigi Miglietti are no longer with us, while David O’Brien stopped training in 1988. He bought a chateau and vineyard in Provence, and his wine earned the same acclaim as his horses once had.

Christy Roche later became a successful trainer, and lives on the Curragh in retirement. “It was the day of a lifetime,” he says, his voice ablaze with nostalgia. “For any jockey, to win a Derby is a life-changing thing.

“Was it my best ride? I don’t know about that; it’s certainly the one everybody remembers. We were a good combination, I had a tough horse who answered every tough question I asked of him. It was a great day. Forty years ago? It feels like yesterday.”

• Visit the Betfred Derby Festival website

On the Derby Beat: Is the Derby at the end of the beginning – or the beginning of the end?

‘Epsom is not where the Jockey Club would like it to be’ – interview with general manager Tom Sammes

View the latest TRC Global Rankings for horses / jockeys / trainers / sires