Our resident movie critic enjoys a 1940s effort from the early stages of a garlanded career featuring High Noon, A Man for All Seasons, From Here to Eternity and The Day of the Jackal

My Brother Talks To Horses (1947)

My Brother Talks To Horses (1947)

directed by Fred Zinnemann; starring Jackie ‘Butch’ Jenkins, Peter Lawford, Charles Ruggles

Without a doubt, the name of Fred Zinnemann belongs on any credible list of the great filmmakers in Hollywood history. Directing High Noon, A Man for All Seasons, From Here to Eternity, Julia, and The Day of the Jackal should be enough to make the case.

But even the great talents must serve their time in the trenches, which is why Zinnemann’s good name is attached to a little movie with a horse racing theme that is much better than it deserves to be, thanks to Fred Zinnemann. The name of the film is My Brother Talks to Horses.

At this point the reader has a right to wonder if their part-time critic has lost his movie marbles. The title alone is warning enough. The screenplay was written by journalist Morton Thompson, based on ‘Lewis, My Brother Who Talked to Horses’, from his collection of newspaper columns and short stories entitled Joe, the Wounded Tennis Player.

The ability of young Lewie Penrose to communicate with horses is more ESP than Mister Ed. A horse hauling a milk wagon whispers something to the lad as he passes in the street while trailed by a pack of dogs attracted by the flapping sole of his shoe.

Lewie hangs around a local racetrack stable, listening to the horses in the shedrow for complaints, gossip, and outright touts. He treats his gift as nothing more than a casual byproduct of being a kid. And he falls madly in love with a racehorse named The Bart.

Lewie hangs around a local racetrack stable, listening to the horses in the shedrow for complaints, gossip, and outright touts. He treats his gift as nothing more than a casual byproduct of being a kid. And he falls madly in love with a racehorse named The Bart.

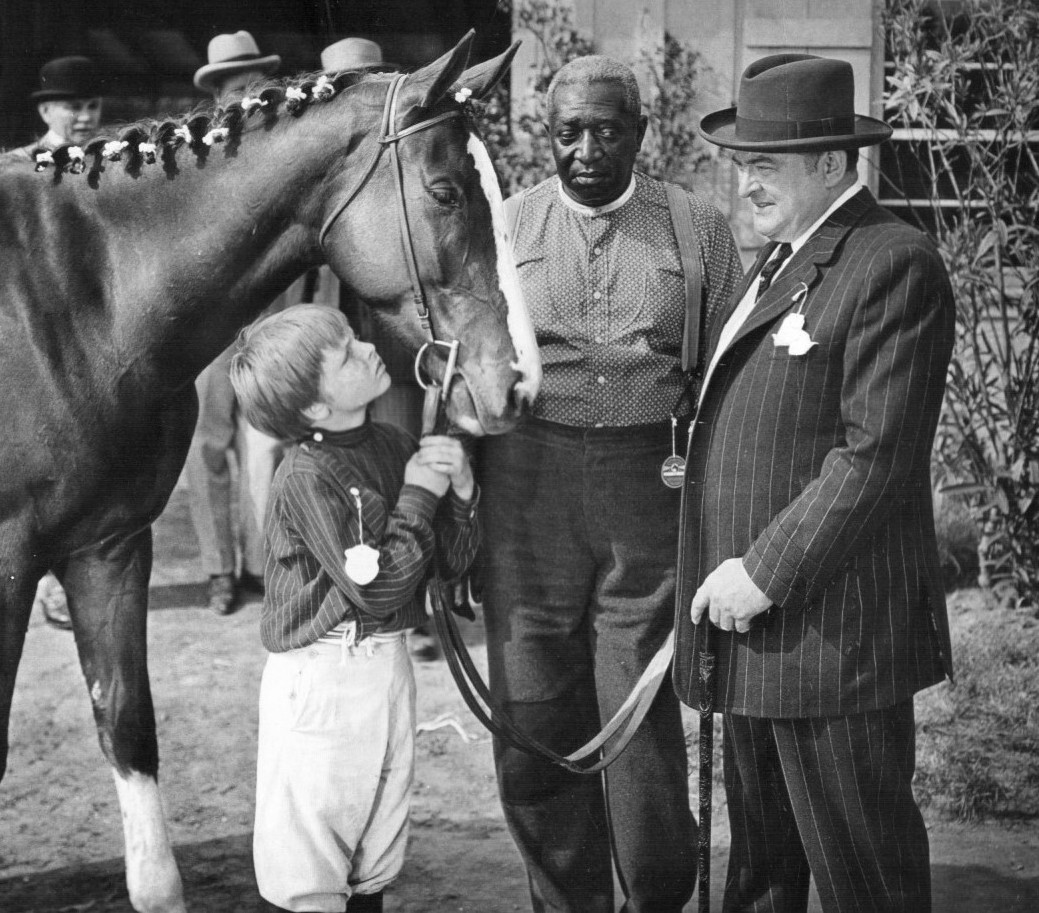

The Bart – version 1.0

Since the film, set in Baltimore, was shot in the 1940s with a turn-of-the-century setting, the real horse named The Bart would not come around until the 1980s when he had the misfortune to be thrown into a West Coast turf environment dominated by John Henry and a host of hard cases like Spence Bay, Bold Tropic, and Galaxy Libra.

Even so, The Bart managed to win a half-dozen graded stakes, including the G1 Hialeah Turf Cup, and come within a hair of beating John Henry in the inaugural Arlington Million. The movie version of The Bart is a claimer who gets dropped in for a tag, breaking Lewie’s heart.

Lewie’s brother, a banker and part-time inventor, conspires with The Bart’s trainer to claim the horse for Lewie, but the horse is roughed up in the race, falls, and breaks a leg. Lewie faints at the sound of the off-screen gunshot. At age 10, I would have, too.

There ensues the single saddest scene ever committed to film in a horse racing movie. Late one night, in a driving rainstorm, Lewie sits on the top rail of a fence staring out at the pasture where he met The Bart every day after school.

Yes, the music swells, but it wasn’t necessary to amplify the deep sense of loss experienced by a child too young to understand its meaning. Zinnemann’s camera follows Lewie’s mournful trudge down the muddy path back home, this time without the laughs of a trailing dog pack.

Against the grain

It is the care taken to present such scenes that elevates My Brother Talks to Horses above the usual B-movie quality of racing movies made during the 1940s. The characters also cut against the grain.

Mr. Mordecai, who could have been a tired cliché of the Black groom, actually runs the stable as head trainer. The professional gamblers hovering around Lewie are a dapper bunch, skeptical of his powers yet anxious to believe.

Lewie’s matronly mother is a health nut who force feeds her family on nature-based meals featuring deer tongue soup and kelp salad. She starts each meal leading a series of lung cleansing yoga exercises. She also is unfazed by her young son’s ability.

“There’s no reason anybody shouldn’t be able to talk to horses if they want to,” she says. “Horses have souls. Personally, I’ve always considered horses very spiritual animals.”

For his part, Lewie is surprised his gift is considered unusual. About horses, he says, “They tell you stuff all the time. If you don’t listen to them it’s not their fault … Horses never kid. They always tell the truth.”

By then, I was convinced the legendary Thoroughbred trainer Allen Jerkens was consulted on the screenplay. I heard him talk like this so often I stopped taking notes.

Believable absurdity

Morton Thompson, the writer, obviously paid his dues around the track. He was a wit in the mold of James Thurber and Robert Benchley, a spinner of tales just tall enough to reach a level of believable absurdity.

Thompson also was a serious chronicler of the medical profession, as proven by his best-selling novel, Not as a Stranger,” pu blished the year after the author’s death, at 45, in 1953. In 1955, Not as a Stranger became a film directed by Stanley Kramer.

blished the year after the author’s death, at 45, in 1953. In 1955, Not as a Stranger became a film directed by Stanley Kramer.

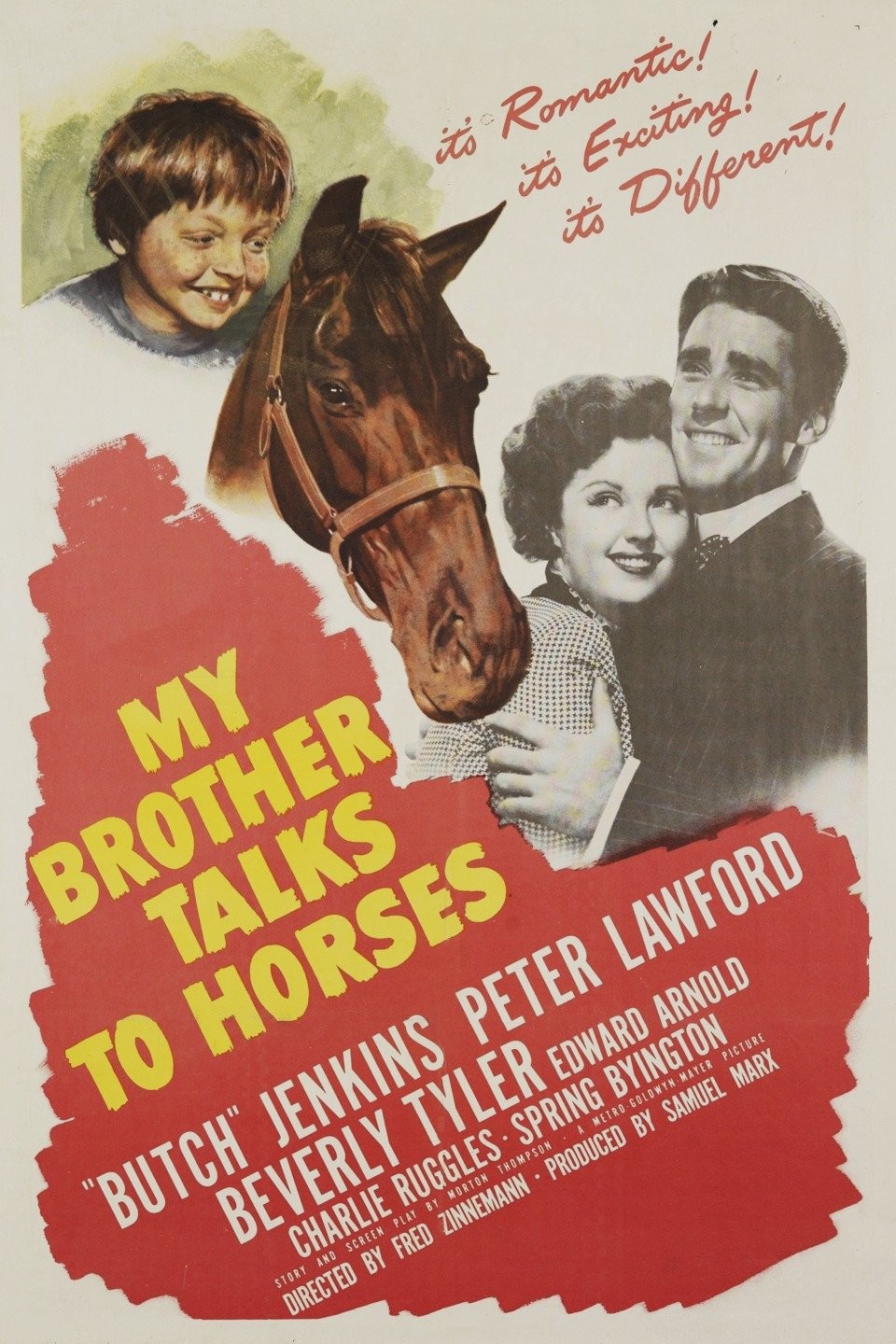

Zinnemann, an Austrian expat, cut his teeth as a director making short subjects for MGM in the the 1930s, including the Oscar winner That Mothers Might Live. Zinneman was on a roll of some serious subjects when the studio bosses hooked him up with their rising child star Jackie ‘Butch’ Jenkins (right) for two assignments, including My Brother Talks to Horses.

Jenkins was already a popular commodity after stealing scenes in National Velvet (1944), as Elizabeth Taylor’s little brother, and Our Vines Have Tender Grapes (1945), with Edward G. Robinson.

Jenkins did not have a long career – reportedly he developed a stutter and quit the business at 11 – but he was a fearless performer who led with a face full of freckles and a buck-toothed grin.

Zinnemann was obligated to display that face in close-ups more than a couple of times, including that moment when the horses come onto the track for the movie’s climactic race. Lewie, in hushed reverence, whispers, “It’s the Preakness,” as if beholding the gates of Valhalla.

gates of Valhalla.

Posh British accent

Peter Lawford plays Lewie’s big brother, barely trying to hide his posh British accent and a little too scrubbed for the part. Beverly Tyler, fresh from a movie with acting prodigy Dean Stockwell, is Lawford’s uptight fiancée, daring to place a bet because Lewie gave the green light.

Veteran character actors Spring Byington, Charlie Ruggles, and Edward Arnold lend credibility to the endeavor, as does Ernest Whitman (Mr. Mordecai), a familiar face and voice in film and radio who often had to settle for ‘uncredited’ roles in mainstream movies of the era.

As for Zinnemann, after working with Butch Jenkins, the stars of the director’s next three films were Montgomery Clift, Robert Ryan, and Marlon Brando, after which he made High Noon with Gary Cooper.

If My Brother Talks to Horses was the price he paid for those opportunities, it was an investment well spent, and a payoff for the audience.

• Watch the movie here

• View all Jay Hovdey’s features in his Favorite Racehorses series

‘The sport deserves a better cinematic version of Secretariat – and so does Secretariat’

View the latest TRC Global Rankings for horses / jockeys / trainers / sires