Our movie correspondent revisits at an all-star blockbuster ‘typical of the romantic comedies churned out by the Hollywood studio system of the 1930s’

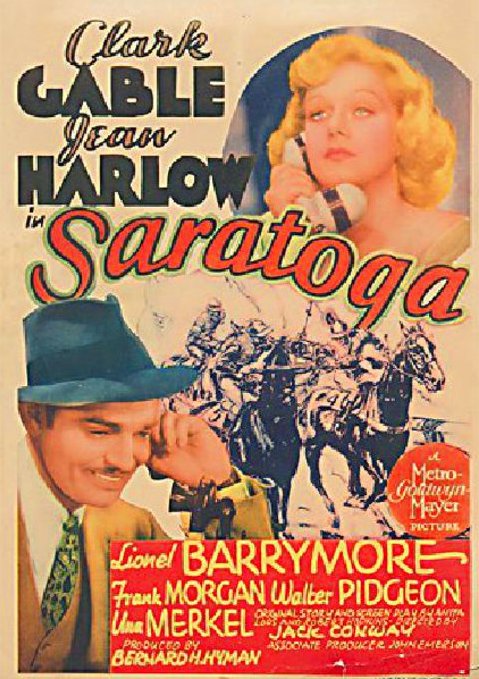

Saratoga (1937)

Saratoga (1937)

directed by Jack Conway; starring Jean Harlow, Clark Gable, Lionel Barrymore

The Saratoga season of 1937 began on Monday, July 26, just three days after the premier of MGM’s hotly anticipated Saratoga, an all-star blockbuster of a film that celebrated horse racing in all its most familiar clichés.

Saratoga, the racing meet, boasted of $181,000 in improvements that included a modern betting ring and a revolutionary photo-finish camera system, along with victories by Burning Star in the Travers, Regal Lily in the Alabama, and Sky Larking in the Hopeful.

Saratoga, the movie, earned $3.5 million in worldwide box office during 1937 to top the list, even though it was not among the nine movies nominated that year for Best Production, nor did it receive nods in any of the other 13 Oscar categories for which it was eligible.

That is because Saratoga is not very good, which is too bad, because Saratoga, the racetrack, deserves a respectably entertaining movie bearing its name. Consider the blast moviegoers had that same year, courtesy of Santa Anita Park, when the Marx Brothers descended upon the young LA racetrack to create A Day at the Races. At that point, Saratoga had been around for 74 years.

Saratoga is typical of the romantic comedies churned out by the Hollywood studio system of the 1930s, and films with a racing theme, no matter how tenuous, were plentiful.

However, just in case the audience was unsure, the musical accompaniment under the opening credits includes a call to the post, then it’s away we go to Lionel Barrymore in full, scene-chewing caricature as a crotchety horse breeder beset by financial woes and yanking a nice looking horse around a studio set passed off as a farm paddock.

We don’t need to wait long for Clark Gable to show up as Duke Bradley, a high-rolling bookmaker with a heart of mush. (Note to Coolmore: there has never been a racehorse named Duke Bradley. Go for it.) It’s Duke to the rescue, settling debts and securing farm ownership for the old breeder and his heirs, which includes a son with a heart condition and a gallivanting granddaughter.

We don’t need to wait long for Clark Gable to show up as Duke Bradley, a high-rolling bookmaker with a heart of mush. (Note to Coolmore: there has never been a racehorse named Duke Bradley. Go for it.) It’s Duke to the rescue, settling debts and securing farm ownership for the old breeder and his heirs, which includes a son with a heart condition and a gallivanting granddaughter.

Enter Jean Harlow.

Gable was rolling at the time, flush from his Oscar role in It Happened One Night and his robust Fletcher Christian in Mutiny on the Bounty, with Gone With the Wind on the near horizon. He was a red-blooded movie star, his characters leering and cracking wise. But Harlow was something else again.

Dangled sexual favors

Think Marilyn or Madonna at their peaks as cultural icons. Harlow was the platinum blonde tease who dangled sexual favors spiced by the kind of double, triple, and quadruple entendres required for adult entertainment at the time.

MGM played her image for all it was worth, working Harlow like a rented mule through 13 starring roles in the five years before Saratoga began production in April of 1937. She had just turned 26.

Before descending into a romantic morass, Saratoga gets off to a promising though predictable start as a horse racing yarn. The

scene of Carol leading her young racehorse into the Saratoga sales ring while wearing an evening gown (Carol, not the horse) is priceless. And there is some good bookie patter when Duke is at work at the races.

scene of Carol leading her young racehorse into the Saratoga sales ring while wearing an evening gown (Carol, not the horse) is priceless. And there is some good bookie patter when Duke is at work at the races.

The race recreations are for the most part forgettable, except when ace jock Dixie Gordon drops Hand-Riding Hurley and faces no stewards’ action as a result. ‘Twas ever thus.

Novice actor Henry Stone plays mild-mannered Hurley, while Gordon is acted with snarling delight by Frankie Yarro, who made a good living playing jockeys through the 1950s; he was Snapper Garrison in an episode of TV’s Bat Masterson.

Pop-eyed subservience

Other familiar faces in the cast include Frank Morgan and Margaret Hamilton, later to be reunited in The Wizard of Oz, and Hattie McDaniel, who gets plenty of choice lines from screenwriter Anita Loos (“Now don’t go having a nervous break-up”) but still must deliver them with the pop-eyed subservience imposed on Black actors typecast as domestics.

Harlow’s Carol Clayton is engaged to Hartley Madison, an upright businessman who likes to place the occasional $5,000 bet on the ponies. Of course, she develops an immediate love-hate crush on Bradley, the bad boy. Stop me if you’ve seen this before.

As played in Saratoga, the bad boy is out to take the businessman for all he can in losing bets, while the girl juggles the fate of grandfather’s farm with her hots for Duke and her flagging interest in the businessman, who is played by Walter Pidgeon and suffers the same sympathetic fate as future cinema cuckolds Ralph Bellamy in His Girl Friday and John Howard in The Philadelphia Story.

Not to pass too much judgment on a relic from a distant time, but the gold-digger motif seemed to be deployed with distasteful abundance in those screwball comedies of yore.

Add to that in Saratoga a truly icky plot turn that blamed Carol’s “nervous condition” on the lack of sexual gratification, no entendre required.

Marrying for money

Then again, marrying for money was considered a career path for sexually suppressed women of the era, and the fantasy was milked by moviemakers for all it was worth. At some point, the dame would get wise and go for the guy who promised true love, if not a summer house in the Hamptons.

Saratoga includes a travelogue of racing locales as Duke, Carol, and a colorful band of horseplayers straight out of central casting railroad around the country. Footage of Hialeah’s flamingos, Santa Anita’s paddock gardens, and the spires of Churchill Downs are little more than namechecks along the way.

The game ends up back at Saratoga, where a plot is hatched around the Hopeful Stakes that involves a heavy-handed jockey switch certain to make the difference in the race. As if.

The game ends up back at Saratoga, where a plot is hatched around the Hopeful Stakes that involves a heavy-handed jockey switch certain to make the difference in the race. As if.

Even before production on Saratoga wrapped, the movie-going public was already being primed for the next Harlow movie. Then on May 29, after struggling to complete a scene in which she was being treated for a cold in a train compartment, Harlow fell desperately ill for real.

Her condition deteriorated quickly, and she died on June 7 from acute kidney failure, complicated by an ongoing infection from dental surgery.

Quaint twist

Studio execs proposed scrapping the movie, or hiring a name star to replace Harlow for the remaining scenes. In a quaint twist, the studio PR department asked the public to weigh in.

The overwhelming sentiment was to complete the movie without a replacement, a problem solved with a Harlow stand-in and a voice actor for dialogue. As a result, there are a handful of scenes in which Carol Clayton’s face is obscured, or lines delivered with her back to the camera.

Since Saratoga was billed as Jean Harlow’s final performance, the audiences went along with the awkward compromise and flocked to the film.

Reviews were mixed. The critic for the New York Herald Tribune watched Saratoga with “a premonition of disaster” and insisted that because Harlow was “looking ill much of the time and striving gallantly to inject into her performance characteristic vigor and vibrancy, the result, in face of subsequent events, is grievous.”

Variety, though, took a more generous approach. Its critic observed that “the audience seemed after the first few scenes to accommodate itself to the fact that it was witnessing a posthumous performance and to give it the same laughter and enjoyment and completely absorbed attention any other meritorious production would command – a genuine tribute to the artist who, gracing the screen for the last time, transcended the circumstance of untimely death.”

• Saratoga is available for a modest fee on several internet sites

• View all Jay Hovdey’s features in his Favorite Racehorses series

‘The sport deserves a better cinematic version of Secretariat – and so does Secretariat’

View the latest TRC Global Rankings for horses / jockeys / trainers / sires