Our resident movie correspondent turns his attentions to an impressionistic fly-on-the-wall documentary characteristic of its director

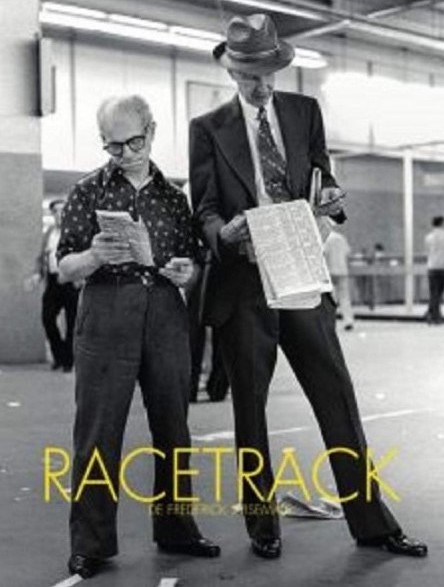

Racetrack (1985)

Racetrack (1985)

directed by Frederick Wiseman

Racetrack is a black-and-white documentary without narration or music shot in 1981 and released in 1985 that didn’t get any serious airtime until PBS picked it up for an evening slot two weeks before the 1986 Belmont Stakes.

Time to eat your vegetables? Not hardly, because Racetrack is both pleasurable and nourishing in so many ways that it would be a shame to leave it off the film viewing list of any serious racing fan.

It was widely praised at the time by mainstream critics who barely knew which end of the horse did the eating, while those in the know were obliged to concede without passing judgment and respond with: “Yep, that’s the racetrack all right.”

Primarily Belmont Park, that is, in all its pre-everything glory, analog to a fault. But what has changed, other than phones that take photos and tell you what Steve had for lunch in Solvang?

Early 1981 was not a simpler time, by any stretch of the imagination. President Ronald Reagan was wounded by a would-be assassin. The first Space Shuttle was launched. Raiders of the Lost Ark came along to insert Indiana Jones into the consciousness.

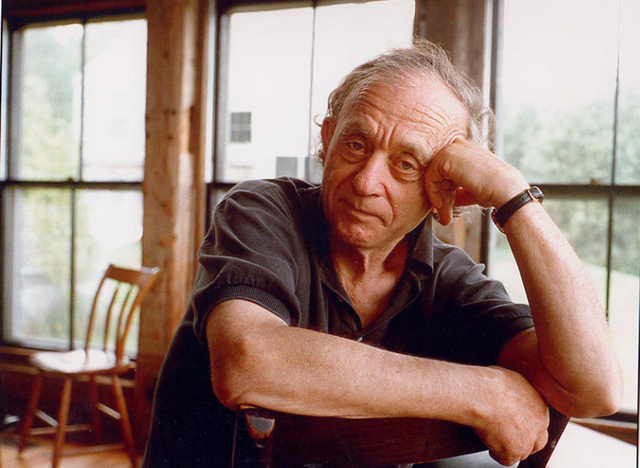

And then there was Frederick Wiseman, already on his 17th feature-length documentary, roaming the Belmont backstretch with cinematographer John Davey in search of … what exactly?

Mordant whimsy

To that point, Wiseman, a native of Massachusetts, had churned out documentaries with such self-explanatory titles as High School, Hospital, Juvenile Court, and Meat. His most recent had been The Store, a work of mordant whimsy that focused on Nieman-Marcus in Dallas, Texas, during holiday shopping, but his most notorious was his first, Titicut Follies, a ghastly look inside a Massachusetts state prison for the criminally insane.

“My movies are more novelistic than journalistic or ideological in their approach,” Wiseman said in a 2014 address at the Documentary Film Institute.

“I always try to reflect the complexity and ambiguity of the place that is the subject of the film, rather than have ideological blinders on and try to present a particular political or social point of view.

“I always try to reflect the complexity and ambiguity of the place that is the subject of the film, rather than have ideological blinders on and try to present a particular political or social point of view.

“I’ve never found any ideology that adequately explains the complex events I’ve come across while making these films.”

Racetrack opens at Sunnyview Farm in Ghent, New York, except that the viewer has no idea of the farm’s identity unless they catch a quick glimpse of the name on the back of jackets worn by some of the staff.

Wiseman’s theme, if there is one, begins at the beginning, and so there is a graphic foaling, mares and babies in the field, and then one of those matings that the kids like to giggle about. It’s not personal. Just business.

Quiet beauty

Since there is no plot to Racetrack, there are no plot spoilers. Instead, the film unveils as a series of moving photographs – some mundane, some in the moment, and some imbued with a quiet beauty, exposing viewers to a world of which few could even dream.

While those unfamiliar with the milieu are coming to terms with the bustle of horses circling the confined space of a shedrow, or the artistry of properly bedding a stall, or the time spent just sitting, sipping a beverage, or playing Pac-Man in the stable rec room, the rest of us will be searching the brain to place names with the many familiar faces captured even briefly by Wiseman’s camera.

Among the jockeys caught at work is apprentice Richie Migliore, who had been riding for all of nine months, not a whisker to his name.

Jacinto Vasquez, Jorge Velasquez, and Jean-Luc Samyn move through the screen, as does Don MacBeth, who died of cancer in April of 1986, just before Racetrack finally aired. There also is an obligatory winning leap from Angel Cordero, Jr., then in mid-career and going strong.

Lenny Imperio opened his barn to Wiseman and let him linger nearby in conversations with agents, veterinarians, and stable crew.

P.G. Johnson and his cigar make a quick cameo. That’s Lou Rondinello, ramrod straight and dressed for success, the picture of the high society trainer.

And Wiseman could not resist the inclusion of an extended monologue delivered to an audie nce of media by Johnny Campo, who was mere days away from an attempt to win the Triple Crown with Pleasant Colony.

nce of media by Johnny Campo, who was mere days away from an attempt to win the Triple Crown with Pleasant Colony.

Timeless quality

But their names are not important, which is why Wiseman’s scenes of the racing world in its natural state have a timeless quality. There is nothing intrinsically interesting about the eating of meals in the stable cafeteria, the mixing of grain at feed time, or impromptu porch picnics during idle afternoon hours, but thank goodness Wiseman was there.

A meeting of jockey agents concerned with insurance coverage is paired with a backstretch chapel service. Veterinarians go about their anonymous work, needles at the ready. A game show or a soap opera playing on a jockeys’ room television shares time and space with a race replay on another.

And that paperback in the hip pocket of the dude shooting pool is Invisible Man, by Ralph Ellison. Of course it is.

John Hennegan, half of the Hennegan Brothers documentary team with his brother Brad, calls Racetrack, “An incredible time capsule.”

He should know. Their work most significantly includes The First Saturday in May (2007), the last word in Kentucky Derby documentaries, and they are currently working on a film about D. Wayne Lukas, arguably the most influential trainer of the late 20th century.

Fly-on-the-wall filmmaking

On the Muscle (2005) by documentarians Robin Rosenthal and Bill Yahraus, comes closest to Wiseman’s spare style of fly-on-the-wall filmmaking. Their season spent with the stable of Richard Mandella provides in many ways a more current bookend to the era evoked in Racetrack.

The scriptless nature of the documentary beast lends itself open to sweet surprise, but none in the experience of this viewer can match that moment captured by John Corey in his 2008 film Lost in the Fog, about the brilliant American sprint champion based in Northern California.

Corey was arriving at the end of the project, with much of the film editied, when it was discovered Lost In The Fog was suffering from inoperable spinal tumors that were being treated by radiation therapy.

Corey was in the office of owner Harry Aleo, a crusty World War II vet who teared up at the mere mention of his colt, when he received a phone call from his trainer, Greg Gilchrist. Corey’s sound was running, with the camera tight on Aleo’s face, as Gilchrist can be heard to say, in a choking voice, “Well, bad news. It’s all over.”

Racetrack works its way to the end of its nearly two hours with three loosely connected set pieces.

Racetrack works its way to the end of its nearly two hours with three loosely connected set pieces.

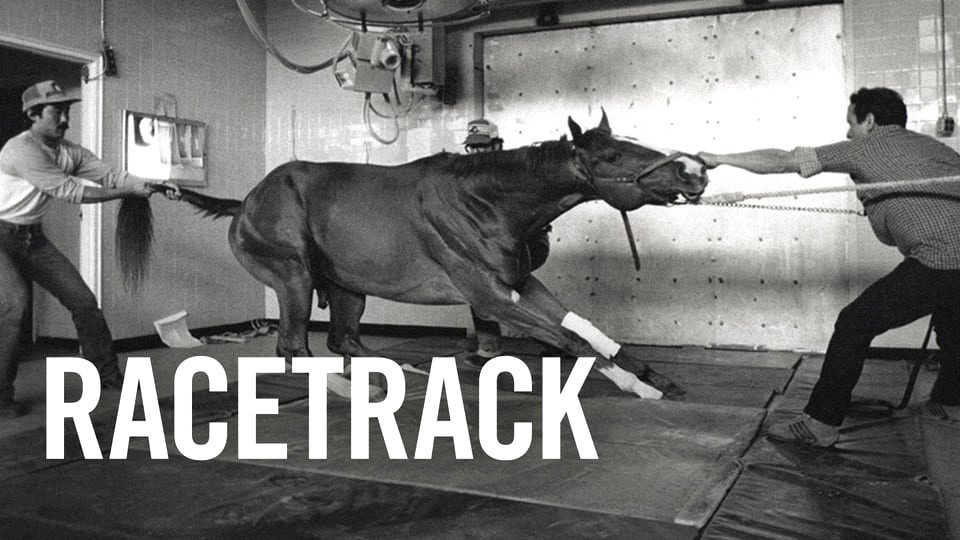

First, there is a soup-to-nuts segment in the local equine clinic as a surgical team anaesthetizes a Thoroughbred and then repairs an ankle fracture, drilling and chipping away at hard bone as if carving a Madonna out of marble.

For the record, the unidentified surgeons are as famous as equine specialists get, being clinic owner William Reed and a very young Larry Bramlage.

Wiseman’s transitions are often abrupt, sometimes even comical. From Dr. Reed’s recovery room the scene moves to the Roseland Ballroom in Manhattan, where the swells of New York racing have gathered to honor John A. Morris, one of their cherished own, a pillar of both the Thoroughbred world and Wall Street.

Social texture of the racing world

Writing in the New York Times, John Corry (different era, different spelling) calls the banquet segment, “the most captivating part of Racetrack … charming, like a Life magazine spread from the 1950s. It is there because Mr. Wiseman wants to say something about the social texture of the racing world, but we enjoy it apart from that.”

The film ends back at the races on a big day at Belmont Park for what turns out to be the Belmont Stakes. Again, there is no labeling of specifics and names are heard only in passing, although Marshall Cassidy’s race call lets the viewer know that Pleasant Colony was beaten by Summing.

Wiseman lingers on the post-race hubbub, eavesdropping on the network interview of winning jockey George Martens by trainer-turned TV analyst Frank Wright, then turns to the crowd’s exodus from the track and the cleaning crew that must deal with the debris left behind.

For added value, there is the fleeting sight of Mr. and Mrs. John A. Morris in front of the clubhouse, waiting for their ride.

“Racetrack is difficult viewing at times, but then the trouble with most television, public and private, is that it’s much too easy,” wrote media critic Tom Shales in the Washington Post.

“In focusing on a specific, quixotic, rather pixilated environment, Wiseman emerges with a new assortment of insights and observations, and that Racetrack could never be adequately summarized in print is part of its brilliance.”

Wiseman is 94 and still at work. His four-hour documentary of a French restaurant, Menus-Plaisirs – Les Troisgros, was released last year.

• Digital versions of 44 Wiseman documentaries are available to rent through his Zipporah Films website, with Racetrack at a pricey $24.95. But if you have a library card—and who doesn’t?—the kanopy.com website has Racetrack there for free.

• Read all Jay Hovdey's features in his Favorite Racehorses series

‘The sport deserves a better cinematic version of Secretariat – and so does Secretariat’

View the latest TRC Global Rankings for horses / jockeys / trainers / sires