Our resident movie correspondent enjoys a nostalgic look as Groucho, Chico and Harpo bring their typical brand of 1930s black-and-white celluloid humour to Santa Anita

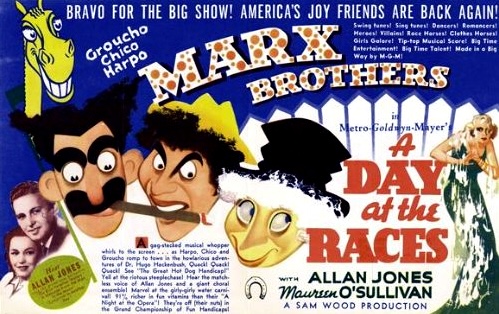

A Day at the Races (1937)

A Day at the Races (1937)

directed by Sam Wood; starring the Marx Brothers, Margaret Dumont, Maureen O’Sullivan

Fans of the fine British racemare Emily Upjohn recently followed their stately star through three years of competition, during which she won stellar events and took on some of the toughest males of the age.

At idle moments, those fans may have wondered at the derivation of her name, and, disappearing down a shallow internet hole, they quickly would have learned that Emily Upjohn was a character created for the Marx Brothers movie A Day at the Races, released in 1937.

If the discovery led in turn to a viewing, the unsuspecting modern filmgoer might have wondered what all the fuss was about, and when, if ever, they were going to get to the races. A Day at the Races offers singing and dancing and extended slapstick routines that verge on the monumentally absurd, wrapped around a wafer-thin plot focused on a financially troubled health sanitarium and its frail but determined owner whose fortunes lie with either an angry, confused racehorse, or the generosity of Emily Upjohn, a world-class hypochondriac of considerable means.

The character is played by Margaret Dumont, a stage actor who stepped away from her career to be a real-life society maven before divorce and death ended two marriages and she went back to work. She landed in a series of movies with the Marx Brothers, playing the dim-but-dignified foil to whichever version of Groucho Marx would show up, all variations on a theme.

“I’m a straight lady, the best in Hollywood,” Dumont told an interviewer in 1937, just after filming A Day at the Races. “There is an art to playing the straight role. You must build up your man but never top him, never steal the laughs.”

“I’m a straight lady, the best in Hollywood,” Dumont told an interviewer in 1937, just after filming A Day at the Races. “There is an art to playing the straight role. You must build up your man but never top him, never steal the laughs.”

Scene-stealing form

Groucho, her man, is in full, scene-stealing form as Dr. Hugo Z. Hackenbush, a veterinarian pretending to be a noted physician who charms Mrs. Upjohn with a bogus diagnosis and treatment. Brothers Chico and Harpo come along for the ride, which finally does end up at Santa Anita Park, in a steeplechase race no less.

At the time of filming, in 1936, Santa Anita had just concluded its second season. The idea of building a massive sporting emporium during the depths of the Great Depression was considered a ridiculous risk, but it was accomplished in large part through the backing of Hollywood studio money and prestige, from the likes of Hal Roach of Laurel & Hardy and Keystone Cops fame.

The track opened its arms to movie productions, including a short feature released in the wake of A Day at the Races, called A Day at Santa Anita, starring the Shirley Temple wannabe Sybil Jason and featuring cameos by Bette Davis, Edward G. Robinson, and Al Jolson.

By 1937, the Marx Brothers were big business. Their popular transition from the vaudeville stage to studio pictures gave them almost carte blanche when it came to the staging of their increasingly complicated slapstick routines.

By the time they got around to A Day at the Races – their seventh film and second for MGM – huge swaths of the running time would be devoted to setpieces that were virtually stand-alone distractions from story continuity.

Holy scripture

For the true Marxian aficionados, those scenes are like pieces from a holy scripture. To their credit, the broad and sometimes cruel aspects of the physical comedy are continually punctuated by Groucho’s wisecracks, provided in A Day at the Races by no fewer than seven credited and uncredited writers.

Among them were a core group already in tune with the Marx Brothers, including the estimable playwright George S. Kaufman, who was slumming profitably in Hollywood. Leon Gordon, among the uncredited, was best known for co-writing the horror classic Freaks (1932).

With great ceremony, in an early scene the heroine is presented a set of Jockey Club papers by her paramour, with the promise that owning a racehorse will save the day. Her reaction – “But what do we want with a horse?” – no doubt has been echoed through the ages.

The horse, he says, is named High Hat, “a gelding out of Honey Lamb, by Blue Bolt.” Later we find it is spelled ‘Hi Hat’ – and believe it or not, even though it is attached to the equine star of a classic Hollywood film, there is no record of a Thoroughbred named Hi Hat in any of the most reputable data bases.

There is not much to the shallow romance between the young protagonists, played by Maureen O’Sullivan and Allan Jones. She was well known at the time as Jane in the Johnny Weissmuller series of Tarzan films, while Jones was a typical movie crooner who became familiar later on in horse racing circles as the husband of the former Mary Florsheim, who raced the Hall of Fame champion Cougar II in the early 1970s.

There is not much to the shallow romance between the young protagonists, played by Maureen O’Sullivan and Allan Jones. She was well known at the time as Jane in the Johnny Weissmuller series of Tarzan films, while Jones was a typical movie crooner who became familiar later on in horse racing circles as the husband of the former Mary Florsheim, who raced the Hall of Fame champion Cougar II in the early 1970s.

The rest of the cast is mere fodder for the antics of the three brothers, but a footnote must be placed alongside the uncredited role of the jockey on Hi Hat’s capable challenger in the climactic race.

Young wrangler

The part went to a young wrangler, just 17, by the name of Richard Farnsworth, who went from a career as a stuntman to play both heavies and heroes in more than 90 films before his death in 2000.

After directing A Night at the Opera and A Day at the Races, studio stalwart Sam Wood got on a roll with Goodbye, Mr. Chips (1939), Our Town (1940), The Pride of the Yankees (1942), and For Whom the Bell Tolls (1943). He died of a heart attack at 56 after filming the western Ambush, in 1950.

Chances are, though, Wood never forgot his immersion in the world of the Marx Brothers, who reluctantly submitted their slapstick routines to their talented director. It was reported that while filming A Day at the Races, Wood became exasperated by their on-set antics and cried out to Groucho: “You can't make an actor out of clay!”

Chances are, though, Wood never forgot his immersion in the world of the Marx Brothers, who reluctantly submitted their slapstick routines to their talented director. It was reported that while filming A Day at the Races, Wood became exasperated by their on-set antics and cried out to Groucho: “You can't make an actor out of clay!”

Groucho’s retort was lightning quick: “Nor a director out of Wood!”

Boisterously joyful

Marx Brothers movies were known for their grab-bag of comedy, lightweight drama, and music. After a dreary detour to a winter carnival musical sequence, highlighted only by virtuosos Chico at the piano and Harpo at the harp, A Day at the Races lands on another musical number that ranks among the most boisterously joyful in film history.

Beginning with a song by Jones at the rundown stable where the boys are hiding Hi Hat from the sheriff, the scene transitions to a sprawling number provided by a troupe of Black actors, singers, and dancers of all ages. A medley includes a poignant arrangement of ‘All God’s Children Got Rhythm’, sung by Ivie Anderson, a big band diva on loan from the Duke Ellington Orchestra.

Then comes a rousing sequence from Arthur White’s Lindy Hoppers, a troupe comprised of contest champion couples, making their movie debut.

You won’t find their names in the credits, but they deserve nothing less. Dancing at a pace of about 270 beats per minute are Dorothy ‘Dot’ Miller and Johnny Innis, Dot’s sister Norma Miller and Leon James, and Willa Mae Ricker and Pettis ‘Snookie’ Beasley.

You won’t find their names in the credits, but they deserve nothing less. Dancing at a pace of about 270 beats per minute are Dorothy ‘Dot’ Miller and Johnny Innis, Dot’s sister Norma Miller and Leon James, and Willa Mae Ricker and Pettis ‘Snookie’ Beasley.

Modern audiences may recoil at a brief dose of blackface used by the brothers to hide in the stable crowd, although there is nothing minstrel show about it. Slathering on axle grease from beneath a horse cart, they engage in a couple of dance moves and then flee, blackface being mocked more than endorsed.

When the action moves wholeheartedly to Santa Anita for a true day at the races featuring Hi Hat’s moment in the sun, nostalgia kicks into high gear.

Those of us with a long-running Santa Anita romance wallow in the many shots of the spanking new grandstand and paddock gardens, to the extent that the actors in the foreground tend to spoil the view.

Live-action Looney Tunes

The big race is little more than a live-action Looney Tunes, without a believable moment but plenty of head-shaking smiles. And guess who wins? The production ends with a parading reprise of ‘All God’s Children’ led by Hi Hat and jockey Harpo, with Groucho alongside proposing marriage to Emily Upjohn.

By 1937, the critics were pretty much inured to the excesses, brilliant and otherwise, of the Marx universe. They would rank each new entry alongside the others, as if analyzing a selection of Monet haystacks to pick apart deviations, both good and bad.

A later generation of film critics would cement the Marx Brothers comedies as foundational to the evolution of the American cinema. The madcap movies of Blake Edwards and the Farrelly brothers, along with actors like Jim Carrey and Will Ferrell, owe a considerable debt.

Not the least of their fans was Roger Ebert, who noted with great fondness that A Day at the Races was the first movie he ever attended while in the company of his father, a fan of Groucho, Harpo, and Chico since their days in vaudeville.

In its most recent list of the 100 greatest comedies, the American Film Institute ranked A Day at the Races at No. 59, just behind Cat Ballou and Diner and ahead of Beverly Hills Cop and Broadcast News.

There are three other Marx Brothers movies on the list, including Duck Soup at No. 5. For some reason, the critics who were polled decided Some Like It Hot deserved the top spot, rather than No. 6, Blazing Saddles, but that’s a whole different horse story.

• A free version of A Day at the Races is available on TUBI, with a few commercial breaks and a warning that it contains “outdated cultural depictions that some viewers might fine offensive”. Amazon Prime also catalogs the film for a nominal price, and without a warning.

• Read all Jay Hovdey's features in his Favorite Racehorses series

‘The sport deserves a better cinematic version of Secretariat – and so does Secretariat’

View the latest TRC Global Rankings for horses / jockeys / trainers / sires