Our movie correspondent gives this turn-of-the-century offering a second chance – but a starry cast and prime source material are not enough to redeem a disappointing effort

Simpatico (2000)

Simpatico (2000)

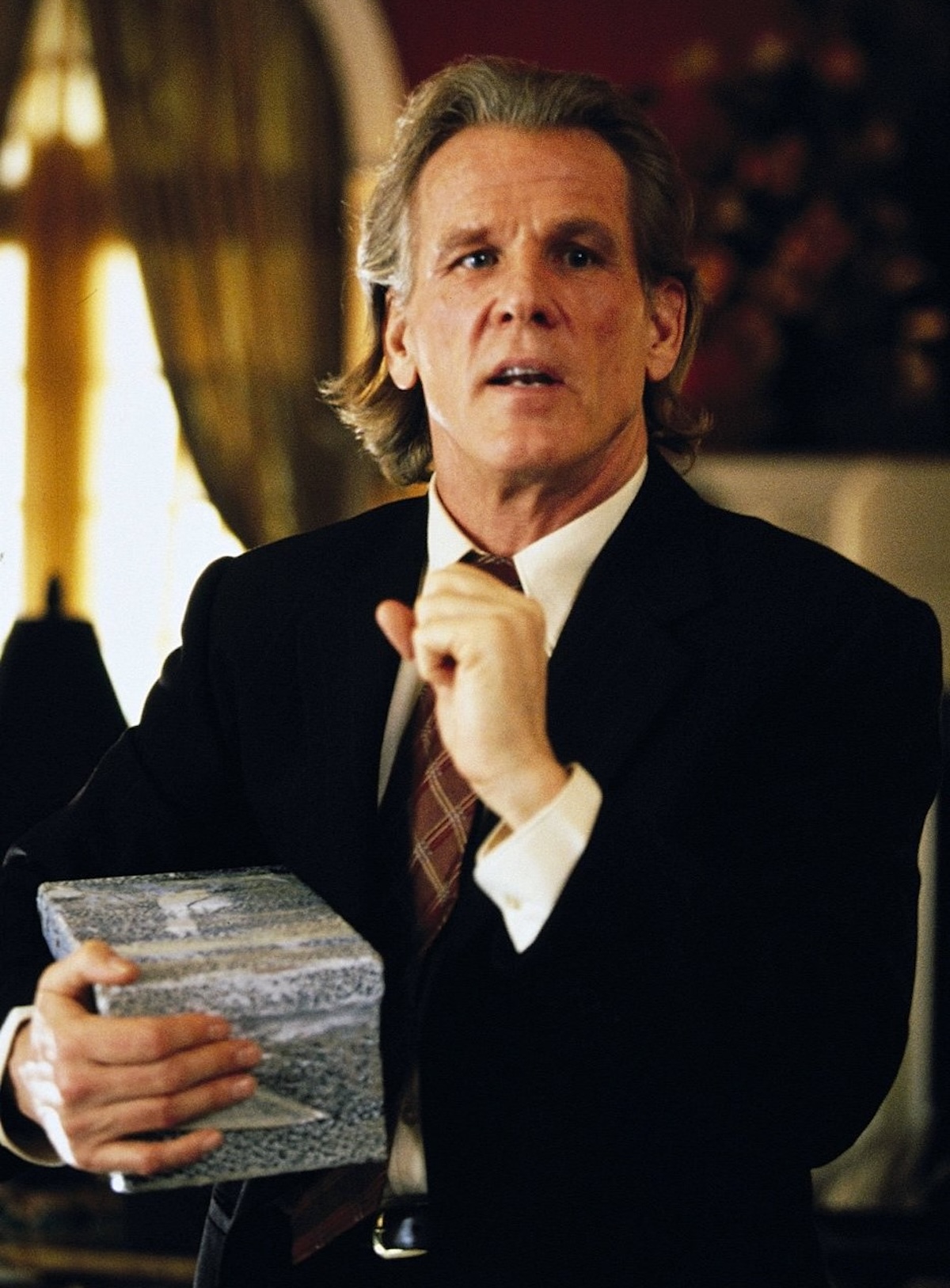

directed by Michael Warchus; starring Jeff Bridges, Nick Nolte, Albert Finney, Sharon Stone

At the turn of the 21st century, there had not been a decent horse racing movie made since Let It Ride in 1989 – and before that Phar Lap in 1983.

That is why there was a certain stirring of anticipation when news got around of an upcoming U.S. release in early 2000 called Simpatico, based on a play by Sam Shepard and starring Nick Nolte and Jeff Bridges, Hollywood hunks who could deliver.

In the end, the failure of Simpatico to endure as anything special lies not with Shepard’s play, even though, in the words of theatre critic Cameron Kelsall, the experience provided “little more than three hours of moral recriminations and unsavory characters”.

In fleshing out the claustrophobic boundaries of the stage version, the filmmakers offered nothing more than a by-the-numbers skimming of the Thoroughbred world beyond the signposts provided by the playwright.

Emotional triangle of greed and guilt

The tale revolves around an emotional triangle of greed and guilt among two men and one shared woman who pulled a horse switch and a betting coup at a California track and got away with it.

The tale revolves around an emotional triangle of greed and guilt among two men and one shared woman who pulled a horse switch and a betting coup at a California track and got away with it.

Years later, one of the men is a successful Thoroughbred breeder in Kentucky married to the woman in the middle, while the odd man out is back in California nursing his existential agonies.

That would be Nolte as Vinnie Webb, clothed in leftover homeless wardrobe from Down and Out in Beverly Hills and rocking the same hairdo he’d wear just a couple years later in his infamous mugshot.

His co-conspirator is Lyle Carter, played by Bridges, married to their girl Rosie while stylishly living a lie and paying off Vinnie, a proven loose horse, to keep his mouth shut.

There is some tight, revealing dialogue between the two men, reminiscent of Shepard’s best stuff from work like True West, which won the Pulitzer Prize, and his screenplay for Paris, Texas.

But then, when the physical restrictions imposed by the play are ‘opened up’, the tone turns to amateur hour at the races, and the viewer is overdosed on the obvious.

Sleazy dealings and bad behavior

Flashbacks to the young versions of the protagonists raise more questions than they answer. Racetrack images flit past in quick, gauzy cuts, suggesting sleazy dealings and bad behavior without context.

In the play, the horse named Simpatico is symbolic, while the movie makes him flesh and blood.

“This isn’t your typical horse,” Carter explains to an indifferent Vinnie. “A Triple Crown winner, $5.4 million in purses, hundred and seventy-five thousand a pop to cover a mare. Syndicated for thirty million. Anyway, I’m selling him tomorrow.”

“This isn’t your typical horse,” Carter explains to an indifferent Vinnie. “A Triple Crown winner, $5.4 million in purses, hundred and seventy-five thousand a pop to cover a mare. Syndicated for thirty million. Anyway, I’m selling him tomorrow.”

In an otherwise humorless landscape, Vinnie’s reply brings a smile: “Yeah, well, y’know … if you need the money.”

The story jerks along in a tangle of loose plot threads and mystifying behavior. Sharon Stone shuffles in as Rosie, groggy and day drunk, to be greeted by a scrubbed and vaguely threatening Vinnie bearing a gift that no one seems to want, namely, a box of photos, negatives and news clippings that have something to do with the long-ago ringer scam and the subsequent blackmailing of a racing commissioner to look the other way.

The photos are, sad to say, kind of tame. Young Vinnie took them from behind a one-way mirror of Rosie, his girlfriend at the time, and Commissioner Simms, played by Albert Finney with his chewy American accent.

The photos are, sad to say, kind of tame. Young Vinnie took them from behind a one-way mirror of Rosie, his girlfriend at the time, and Commissioner Simms, played by Albert Finney with his chewy American accent.

If they were hoping to depict the commish in an assault, it’s far from conclusive. Later, we glimpse headlines that state Simms was disgraced because of corrupt acts as commissioner, not sexual scandal.

Whatever the reason, it was bad enough for him to blow town and change his name, while still tempting fate by staying in the racing business. As a bloodstock advisor, no less.

Simms at first throws cold water on Vinnie’s plan to bring down Carter. And we don’t blame him. It makes no sense.

Empire built on lies

Apparently, Shepard’s play aims to wallow in some murky film noir switchbacks and confusions, and the movie tries to follow suit. Vinnie urges Simms to clear his name by taking possession of the box of evidence and revealing Carter as a crook whose empire is built on lies.

“I’m so completely absorbed in my work that the outside world has disappeared,” says Simms. “It’s vanished, Mr. Webb. I’m no longer seduced by its moaning and fanfare. I’m busy … with the Sport of Kings.”

“I’m so completely absorbed in my work that the outside world has disappeared,” says Simms. “It’s vanished, Mr. Webb. I’m no longer seduced by its moaning and fanfare. I’m busy … with the Sport of Kings.”

Vinnie is flummoxed and wanders off. He was ready to throw himself at the mercy of his fates.

Then, in another odd turn, it seems like Simms has changed his mind. With the evidence – by now nothing more than a Hitchcock-style MacGuffin – Simms thinks he could protect his own dark past while ruining Carter. Then he calls Carter to tell him what’s going on, and at that point the viewer just wants to cry uncle.

Catherine Keener, as Vinnie’s platonic squeeze Cecilia back in LA, is injected by a desperate Carter into the Kentucky morass as a one-person Greek chorus of off-kilter conscience. She offers Simms a bag of Carter’s cash for the photos the commissioner does not possess. She is appalled at the soft-core photos in the box but then forgives Simms since he was “set up”, as if someone else pulled down his pants.

Simms offers to take her to the Kentucky Derby – ringing a needless bell from an earlier scene – or, better yet, flee with him to an island paradise. It’s a corny turn, but not nearly as contrived as the sight of Rosie, dressed in a crimson gown, saddled up on Simpatico with the consent of what has to be the most irresponsible stallion manager in the history of the profession.

Simms offers to take her to the Kentucky Derby – ringing a needless bell from an earlier scene – or, better yet, flee with him to an island paradise. It’s a corny turn, but not nearly as contrived as the sight of Rosie, dressed in a crimson gown, saddled up on Simpatico with the consent of what has to be the most irresponsible stallion manager in the history of the profession.

Ticking time bomb

Carter earlier confessed to his wife that the horse is a ticking time bomb of sterility, and that the new owners – vaguely Middle Eastern – will surely render Simpatico to dog food once they’ve collected on the insurance. (No, they wouldn’t, but never mind.)

A distraught Rosie rides the stallion to the far reaches of the farm, jumps off and whispers some sweet somethings in his ear, then pulls a gun and shoots him dead. (Billy Budd immediately comes to mind, as the sacrifice of an innocent in the face of evil, but don’t blame Melville for this.)

Meanwhile, back in dusty California, Carter and Vinnie are perched on a bluff overlooking the 210 freeway setting fire to the contents of the ubiquitous box. Thank goodness. Time passes, and Cecilia waltzes into Churchill Downs seven months later for the Kentucky Derby, luminous in her white Kentucky Derby dress, as “The Games People Play” plays over the credits, but not the Joe South version. Our loss.

Meanwhile, back in dusty California, Carter and Vinnie are perched on a bluff overlooking the 210 freeway setting fire to the contents of the ubiquitous box. Thank goodness. Time passes, and Cecilia waltzes into Churchill Downs seven months later for the Kentucky Derby, luminous in her white Kentucky Derby dress, as “The Games People Play” plays over the credits, but not the Joe South version. Our loss.

Simpatico was directed and co-written by Michael Warchus, who was making his first movie after taking time off from his regular job as a distinguished director of top-class British theatre productions.

“I’d never been to America until a few years ago,” Warchus confessed to theatre critic Don Shewey when the film was released.

“I’d never been to a horse race, and I didn’t know anything about horses. In writing the screenplay, I was very conscious of areas where there needed to be new material, and I didn’t have the knowledge and vocabulary. Much of the research I did was to acquire that.”

I guess that counts as fair warning.

Around the time Simpatico was being filmed, Shepard was doing more acting than writing, and he was convincing as trainer Frank Whiteley in the TV movie Ruffian (2007). Bridges, by then immortalized in The Big Lebowski, was just as compelling as Charles S. Howard in Seabiscuit (2003). And Nolte, who was fresh from an Oscar nomination for Affliction (1999), went on to channel Jack Van Berg by way of John Wayne as trainer Walter Smith in the HBO series Luck (2011).

As for Albert Finney, he never needed to prove his racing bona fides. As the son of a British bookmaker, he had the game running in his veins. For good measure, Finney also was part-owner of a number of Thoroughbreds, including American champion Slew o’ Gold.

As for Albert Finney, he never needed to prove his racing bona fides. As the son of a British bookmaker, he had the game running in his veins. For good measure, Finney also was part-owner of a number of Thoroughbreds, including American champion Slew o’ Gold.

Critical scorn

Simpatico received near-universal critical scorn, dismissed by Robert Ebert as “the kind of B-movie plot that used to clock in at 75 minutes on the bottom half of a double bill”.

Stephen Holden nailed it in the New York Times when he wrote “The movie is so careless about its horse-selling subplot that its melodramatic payoff feels cheap and abrupt.”

But Charles Taylor, writing in Salon, admired the performances of Nolte and Bridges, and praised the work of Warchus and his cinematographer, John Toll (already a two-time Oscar winner).

Taylor even went so far as to apply wider meaning to the whole endeavor, stating: “The power of a horse race is always pitched right on the edge of pathos because the strength and speed of the horses – all of it in those long, spindly legs – is so fragile. It's hard not to feel the ugliness of corruption when it touches these beautiful creatures.”

On that we all can agree.

• Read all Jay Hovdey's features in his Favorite Racehorses series

Romantic fatalism, honest and free from phony melodrama – Jay Hovdey on Lean On Pete

Henry Fonda double bill: when a celluloid hero tried his hand at horse racing – twice in two years

‘A bulletproof, gold-plated classic’ – Jay Hovdey on Let It Ride

View the latest TRC Global Rankings for horses / jockeys / trainers / sires