It was the first running of York Racecourse’s biggest race – and it produced one of the greatest shocks in European racing history.

The Benson & Hedges Gold Cup run at York on Aug. 15, 1972 had more plot-lines than a Shakespeare comedy.

This was the first running of the race, now known as the Juddmonte International, one of the classiest races of the calendar (and whose 2014 renewal will run on Wednesday). And, appropriately for a contest over the same ground as the famous match between Voltigeur and The Flying Dutchman in 1851, for a period, it had been considered a possible stage for the great rematch between Mill Reef and Brigadier Gerard.

By summer 1972, that pair – both 4-year-olds – had established themselves as two of the all-time greats. Mill Reef, bred and owned by American philanthropist Paul Mellon and trained by Ian Balding, had won five of his six races as a 2-year-old. Brigadier Gerard, an unfashionably-bred son of Queen’s Hussar bred in England and owned by John and Jean Hislop and trained by Dick Hern, had won all four of his.

Both had enjoyed stellar 3-year-old seasons, Mill Reef landing the Epsom Derby (12 furlongs), Eclipse Stakes (10 furlongs), King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes (12 furlongs), and Prix de l‘Arc de Triomphe (12 furlongs); and Brigadier Gerard several big races including the St James’s Palace Stakes, Sussex Stakes, and Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (all one mile), and Champion Stakes (10 furlongs).

Glittering careers indeed, but the only time they went head-to-head, in the 1971 2,000 Guineas (one mile), Brigadier Gerard had beaten Mill Reef by three lengths.

To widespread delight, both horses were kept in training as 4-year-olds, and the prospect of a return match obsessed racing fans through the spring and summer of 1972.

In May, Brigadier Gerard won the Lockinge Stakes (one mile) and Westbury Stakes (10 furlongs) to preserve his unbeaten record, and Mill Reef landed the Prix Ganay (10 furlongs) by 10 lengths. Although victorious in the Coronation Cup (12 furlongs), Mill Reef's desperate neck finish over Homeric inevitably triggered speculation that the horse was unwell.

With Mill Reef sidelined, Brigadier Gerard then won the Prince of Wales’s Stakes (10 furlongs), Eclipse Stakes (10 furlongs), and King George (12 furlongs).

Both horses had a huge following, and the announcement that each would then be aimed at the first running of the Benson & Hedges Gold Cup over 10 ½ furlongs set both camps into paroxysms of glee – only for the feverish anticipation to evaporate like a burst balloon just days before the race when Mill Reef suffered a minor setback in training and was declared a non-runner.

That left the York race a shoo-in for the Brigadier. He was unbeaten in 15 races – only one short of the record then jointly held by the great Italian colt Ribot and American Triple Crown winner Citation – and his cause did not appear to be much threatened by the opposition, headed by 3-year-olds Roberto and Rheingold, trained by Vincent O’Brien and Barry Hills, respectively. This pair had engaged in a hammer-and-tongs finish to that year’s Epsom Derby, Roberto prevailing by a short head under a frenetic drive from Lester Piggott.

But, on his first outing after the Derby, Roberto had flopped in the Irish Derby, and many were convinced that the colt had not recovered from the Piggott tirade.

Piggott himself, never one to let sentiment affect his judgement, elected to desert his sixth Derby winner in favour of Rheingold, the horse he had beaten at Epsom, and he later explained his thinking:

“As with all his horses, Vincent was prepared to run Roberto in this valuable new race only if all conditions were exactly right and would not commit himself until quite close to the day of the race. So, when Barry Hills asked if I would ride Rheingold, who following his narrow defeat in the Derby had been a brilliant winner of the Grand Prix de Saint-Cloud (I was third on Hard To Beat), I agreed readily. I reasoned that the flat, galloping track at York would suit this big, long-striding horse much better than Epsom, but even so, I did not much fancy our chances against Brigadier Gerard.”

Bereft of a jockey, Roberto’s owner John Galbreath – who had named the colt after Roberto Clemente, star player of the Galbreath-owned baseball team the Pittsburgh Pirates – first approached Bill Williamson, the Australian jockey controversially “jocked off” by Piggott before the Derby. When Williamson proved unavailable, Galbreath had a bright, but highly unorthodox, idea. With O’Brien’s agreement, he brought over crack American-based Panamanian rider Braulio Baeza, who rode regularly for Galbreath’s Darby Dan Farm in the U.S., but had never ridden in Europe. He arrived in England on the Sunday, two days before the Benson & Hedges, and first sat on Roberto on the morning of the race.

Baeza recently recalled that, before York, he knew “not a thing about the horse,” other than that he had won the Derby. But Vincent O’Brien was typically assiduous in briefing the new jockey on Roberto’s previous runnings.

“Then I said, ‘But I leave it to you how you ride him,’” the late, great trainer once related of his first session with Baeza – advice that was to prove invaluable.

The decision to put Baeza up on the Derby winner seemed in some quarters to underline the paucity of Roberto’s prospects, or so the betting public believed: He started third favourite at 12-to-1, an insulting price for any Derby winner. Brigadier Gerard, for whom defeat was not an option, went off 1-to-3 favourite, with Rheingold on 7-to-2 (a difference from Roberto’s price, which if you discarded the latter’s dismal Irish Derby effort, defied logic). The other two runners in a five-horse field were Bright Beam (previously Mill Reef’s pacemaker), and Gold Rod, beaten a length by the Brigadier in the Eclipse Stakes.

Brigadier Gerard was one of those horses who light up a racing life, a horse that people will flock to see in action, and a crowd of some 35,000 enthusiasts packed into York that Tuesday afternoon. Among them, if less crammed in than most, was Queen Elizabeth II, the first reigning monarch to visit York races since Charles I, nearly three and a half centuries earlier.

There is a line in the P.G. Wodehouse novel The Inimitable Jeeves that describes a horse race featuring a hot favourite: “In the case of this particular dashed animal, one had come to look on the running of the race as a pure formality, a sort of quaint, old-world ceremony to be gone through before one sauntered up to the bookie and collected.”

So, as the five runners were loaded into the stalls on the far side of the Knavesmire for that first Benson & Hedges Gold Cup, the imminent race had the feel of a simple ritual – a coronation – to be played out before Brigadier Gerard won his 16th race in a 16-race career.

Forty-two years on, Baeza recalled what happened in the first few seconds of the race: “First sixteenth [of a mile], no one was taking the lead, so I let him go.”

Simple as that – but Roberto in “let-go” mode that day was some sight. He maintained a relentless gallop through the first three furlongs, as Bright Beam tried to keep him company, with Brigadier Gerard and Rheingold behind.

As they swung into the long York straight, Roberto was showing no sign of flagging, and with a half mile to go, Bright Beam had been burned off and Rheingold was struggling. But the Brigadier was starting to close on the leader, who was still barrelling along relentlessly, Baeza crouched low in the saddle in the manner that then distinguished American jockeys.

With under a quarter of a mile to run, Brigadier Gerard had cut the deficit to little more than a length, and it looked to his legions of supporters that – phew! – he would catch Roberto and go on to a hard-fought, but decisive victory.

A few seconds later the unthinkable truth hit them. Roberto was finding more, and seemed to be easily keeping Joe Mercer and the Brigadier at bay – a famous moment in English racing history crisply summarised by Braulio Baeza himself: “When Brigadier Gerard came to me, I had plenty of horse left. Nice and handy. So when I set him down, he just pulled away.”

Roberto pulled away so decisively that Joe Mercer quickly accepted the situation and eased off. At the line, Brigadier Gerard was three lengths adrift, with Gold Rod 10 lengths further back in third. Television viewers watched in disbelief as commentator John Penney declared that “Brigadier Gerard’s unbeaten record is absolutely smashed to smithereens,” while the noise on the Knavesmire shifted from delirious excitement to frantic alarm to a massive communal groan.

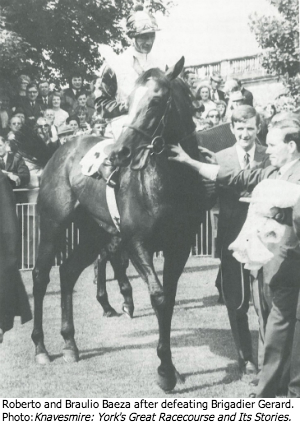

While defeat was a crushing blow to Brigadier fans, few at York that day would dispute that Roberto and his jockey had both produced performances of the highest class – an impression confirmed when the time of the race was announced: 2 minutes, 7.1 seconds, a course record.

Considering the blanket support for the Brigadier, Baeza can be forgiven his apprehension as he came back to the winner’s enclosure.

“There were a lot of people running towards me, and I thought they wanted to kill me, but they were just happy and they wanted to touch the horse and me,” Baeza remembered– further evidence of the generosity of spirit of the English race crowd, who had not seen what they had come to see, but none the less appreciated and applauded what they had witnessed.

Less generous was the post-race comment of Brigadier Gerard’s co-owner Jean Hislop, who sourly observed of the only horse ever to beat her champion that Roberto “must have been stung by a bee.” A more likely clue to the Brigadier’s below-par performance came after the horse had returned to the racecourse stables, where he put his head down and ejected from one nostril a large clot of mucus, which must have been impairing his breathing.

Less generous was the post-race comment of Brigadier Gerard’s co-owner Jean Hislop, who sourly observed of the only horse ever to beat her champion that Roberto “must have been stung by a bee.” A more likely clue to the Brigadier’s below-par performance came after the horse had returned to the racecourse stables, where he put his head down and ejected from one nostril a large clot of mucus, which must have been impairing his breathing.

In any case, was the Brigadier’s performance significantly below par? He had run a gallant race, but was outgunned on the day by a horse described by Piggott as “a champion when things were in his favour,” and by an outstanding piece of jockeyship. Nevertheless, by beating the Brigadier, Roberto was destined to suffer the same sort of innocent infamy as Blame after beating Zenyatta or Red Rum after catching Crisp (though “Rummy,” who went on to win three Grand Nationals, was later forgiven).

After being presented to the Queen, Baeza was whisked away: The following day he was due at Saratoga Race Course, where on the previously unbeaten Linda’s Chief, he was defeated by an imposing chestnut colt having his first stakes win – Secretariat. He never rode in Britain again.

As for Roberto, his chequered career continued. Again ridden by Baeza, he was beaten in the Prix Niel and Arc, both at Longchamp; and as a 4-year-old, he ran three races, in all of which he was partnered by Piggott: second at Leopardstown, then an easy winner of the Coronation Cup, then unplaced in the King George.

Nor was Brigadier Gerard finished. In autumn 1972, he bounced back from his sole defeat by winning the Queen Elizabeth II Stakes at Ascot, then ended his glorious career with a smooth victory over Riverman in the Champion Stakes at Newmarket.

The sensational first running of the Benson & Hedges Gold Cup set the tone for other 1970s renewals, with odds-on favourites beaten in 1973 (Rheingold at 4-to-6), 1975 (Grundy at 4-to-9), 1976 (Trepan at 10-to-11), and 1977 (Artaius at 8-to-11).

But for drama, excitement, and mixed emotions, none of those later races compares with the very first running, when the Knavesmire was watered with the tears of Brigadier Gerard devotees, and when Roberto and Baeza left scorch marks on the Yorkshire turf.