In 1982, a few men steeled to make the movie of an Australian national treasure. With an enormous, taxpayer-funded budget, in August 1983 they released "Phar Lap." To this day, it remains the nation’s favourite horse flick, a film entrenched in the musty legendry of its subject matter. Jessica Owers revisits racing’s most iconic feature film.

It was a fantastical tale, and John Sexton knew it.

“It’s the sort of story, really, that we wouldn’t have been game to invent unless it was true,” he said.

Sexton, an executive producer, was sitting on the biggest-budget film Australia had ever seen, and it just happened to be about a racehorse. The year was 1983, and the film was “Phar Lap.”

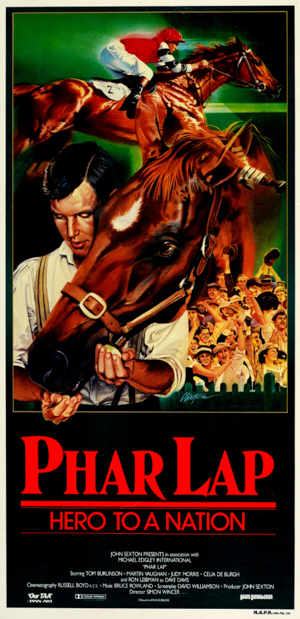

At $7 million, it was history-books expensive. Directed by Simon Wincer, adapted for the screen by David Williamson, “Phar Lap” was a deep well of Australia’s finest in film. There were photographers Russell Boyd and Keith Wagstaff, musician Bruce Rowland, and actor Tom Burlinson, still in the headlights of “The Man From Snowy River.” And, in the starring role, there was the very big Towering Inferno, plucked from a farm in the New England pastures of northern New South Wales.

“Phar Lap” was released to Australian audiences on Aug. 11, 1983. It recreated the story of the nation’s favourite Thoroughbred, a tale that had been told and retold in rich, rarely exaggerated detail since 1932. The film’s publicity machine had a bottomless tank of fuel. There were parties, press events, and wall-to-wall merchandising. Close your eyes, and it might have been 1930 all over again. Like Phar Lap, Towering Inferno was everywhere, whisked from city to city with hired heavies and a media entourage. Within 11 weeks, the film had returned its costs at the box office, and begun the slow creep into horse-movie immortality.

Sexton had set his mind to “Phar Lap” in 1980 when his father had recounted for him the rousing cheers at Flemington as the real horse won the Melbourne Cup. Sexton hadn’t known his father had been in the crowd that day in 1930, nor had he given it much thought. After all, if you weren’t a racing fan, Phar Lap’s story was just another in the long annals of Australia’s sporting history. But Sexton had a good nose for content. He was a former “Four Corners” reporter, and the Phar Lap story seemed to have it all – highs, lows, conflict, fame, and glory.

“It had all those elements,” he said, “and it was all true.”

“It had all those elements,” he said, “and it was all true.”

“Phar Lap” began shooting in mid 1982. It was financed by a federal government tax break, which stipulated that filming had to be wrapped up by Christmas that year. Over 60 days, or 10 six-day weeks, the production travelled from locations in Sydney to Melbourne and in between, and lastly to Brisbane, where the final scene was shot only days before Christmas.

At once, the production was loyal to its racing roots. Australian jockey Roy Higgins, then still riding, was aboard as technical advisor for racing, and he oversaw the recreation of Phar Lap’s mighty turf deeds. Without a mechanical horse in sight, jockeys from Sydney, Canberra, and Melbourne steered retired Thoroughbreds through dramatic galloping scenes with camera cars and megaphones in their road. Higgins was determined that the races be as authentic as possible; not only true to the style in which Phar Lap won, but also shot without races looking choreographed.

“I was teaching the horses to be champions, and the jockeys to be actors,” Higgins said.

Many of his jockeys were professional riders, moonlighting on set between race meetings. Ron Quinton was among them, as was Kevin Moses and Harold Light. But, though filming of the major race scenes occurred largely in Melbourne, and primarily at Caulfield, it often proved difficult to pry riders away from mid-week commitments. On one occasion, a contingent of jockeys arrived from Canberra when producers ran short of riders for a Wednesday shoot.

None of this came cheap. Sexton put aside $500,000 of the budget for the horses alone, which included their purchase (he had them for six months), their board, and their training. The actors’ bill was $600,000, including $250,000 for the extras (such as the jockeys). The crew costs came to $400,000, and while this doesn’t seem like much in today’s world, it was a lot for a local production in 1982. During the film’s race scenes, for example, there were 600 people lined up at the canteen.

In total, the production purchased about 45 horses. Most were retired or re-educated Thoroughbreds, wise to the running rail, yet fit enough to run three and four times a day. Very few had any film experience, including Towering Inferno, and horse trainer Evanna Harris recalled he was the hardest horse she had ever had to school for a set.

“He was nine or 10 when I got him, and he’d never had much work, never been off the property,” Harris said. “He was very set in his ways, and very unresponsive.”

Towering Inferno became pliable with training. In temperament, he wasn’t unlike the real Phar Lap, doe-eyed and docile. But Tommy Woodcock, Phar Lap’s strapper in the 1930s, and the man that cradled the champion through his tough, short life, recalled that Towering Inferno was also a nice replica of the original.

“He is a Thoroughbred in looks, but he has got bad hocks,” Woodcock told journalist Bert Lillye for the Sydney Morning Herald. “Still, they couldn’t get everything perfect, could they? But he is a big brute. Phar Lap wasn’t handsome either. He was plain, just like this big coot. But he sure could gallop.”

Towering Inferno was Thoroughbred on his sire’s side, but that was as close as he had ever got to a racecourse before Sexton’s clappers rolled up. He became an incredibly valuable horse, reportedly insured for $7 million during production (the total cost of the film), and far too important to risk during race scenes. He was replaced, instead, by the experienced Shivers, who acted as his galloping double. Shivers belonged to Harris, and though he was of similar size to Towering Inferno, he required four hours in make-up before hitting his straps on the track.

Unlike many racing movies these days, “Phar Lap” paid very close attention to its racing accuracy. Sexton wanted his big scenes, especially the 1930 Melbourne Cup and the 1932 Agua Caliente Handicap, to be authentic in almost every way. Track directions, jockey silks, and finishing margins... these were high on his agenda, and he employed some of the best horsemen in Australia to achieve them.

There were eight wranglers on duty during filming. Among them was Gerald Egan. Since “Phar Lap,” Egan has apprenticed jockeys Luke Nolen and Nicholas Hall from his high-country headquarters in Mansfield. But in 1982, he doubled for Tom Burlinson, as well as joining the ruck of the racing. Egan’s most famous scene in the film is the training session in Centennial Park, beautifully filmed but a gross exaggeration (or simplification) of how Phar Lap learned to run.

Sexton said there was little license taken with the plot. It’s hard to imagine that the shy, correct Woodcock ever tore down trainer Harry Telford about Phar Lap’s condition, and yet the strapper advised the set that it occurred. Likewise, when Phar Lap is named “Lightning” by an Asian gentleman, it also occurred. In the DVD release, Burlinson says Woodcock believed the film was 90 percent true to tale. The film is richer for Woodcock’s input, because he died less than two years after its release.

The production traversed the east of Australia through its 60-day schedule. The very first scene captured was in the Sydney suburb of Newtown, when Woodcock confronts trainer Harry Telford about finding Phar Lap tethered and exhausted in his box. Thereafter, the production moved through Randwick, Flemington, and Caulfield, each hauled back in time 50 years, while quaint Towong Racecourse in rural Victoria was used for Phar Lap’s first race. The old barn at Inglis’s Newmarket complex was Telford’s Sydney stable (though in reality, Telford would never have been able to afford the rent on such a large space), while Centennial Park, La Perouse (the beach scenes), and the sand dunes of Cronulla all hosted memorable moments. Adaminaby racecourse, in the Snowy River, became 1932 Mexico, and Phar Lap’s emotional death was recreated at the Highlands Equestrian Centre in Sutton Forest, two hours south of Sydney. The final shots were filmed during Christmas week at St Joseph’s College in Brisbane, which doubled as the Agua Caliente hippodrome with its Spanish-inspired facade.

Sexton’s art department had 15 percent of the total budget to recreate 1930s Australia. Along with set building, that covered the removal of contemporary features like billboards, antennas, and parking signs. But it wasn’t always possible to hide everything, in particular the lofty skylines of both Sydney and Melbourne (for this reason, Caulfield played host to many of the races). In one scene, the pointy end of Centre Point Tower is visible, and the Harbour Bridge is pictured completed in 1928, when, in fact, the arches didn’t meet until August 1930.

But largely, “Phar Lap” looks and feels like Australia of old, a credit to the production designer Laurence Eastwood. This was complemented by a jaunty period soundtrack at times, and exceptional costume design by Anna Senior.

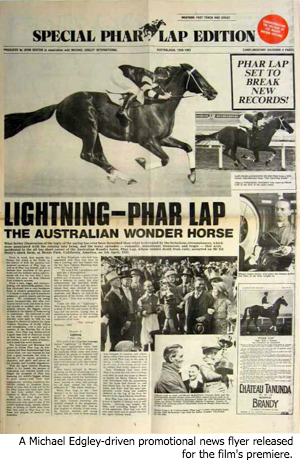

Post-production began almost immediately after the cameras stopped rolling in December 1983. By the end of June the following year, the reels were complete. Michael Edgley stepped in to promote the film, spurred by his fresh success with “The Man From Snowy River,” and he was relentless. He hosted an enormous launch bash in his Point Piper home on Sydney Harbour, with fireworks, tinsel, and goodie bags. In August, the film released to local audiences, and even if Edgley wasn’t delighted with the figures, he never said so.

“Phar Lap” grossed $9,258,884 in the Australian box office. Sexton, Wincer, and Edgley had expected it would outstrip “The Man From Snowy River” at $17 million, but it fell far short. Nevertheless, by 1984 it was the second-highest grossing Australian film of all time (in 1986, “Crocodile Dundee” destroyed them all), and today it is 27th on that list.

Reviews were mixed. Many were glowing, wallowing in a story that almost every Australian child is raised with. Others bemoaned the dramatization of it, perhaps not realizing it was virtually true to tale, or criticized the recycling of figures from still-fresh “Snowy River”. This Canberra Times critic was especially scathing:

“‘Phar Lap’ is a fine film for children or Queenslanders, or for anyone who is able to put themselves into a childish or Queenslandish state of mind. But as someone who has had his brain addled by an excess of education... I could not make myself quite simple enough to enjoy ‘Phar Lap’ to the full.”

Sexton believed the film was a satisfactory success in Australia, and in 1984 he pursued its release in the United States. However, there was an enormous white elephant about the chronology of the Australian version, and that was Phar Lap’s death. It occurred at the beginning of the film, Wincer and Sexton not wanting Australian audiences, who obviously knew the ending, to be waiting anxiously for the sad inevitable.

In the U.S., there were few that knew the sensational, heart-busting end that Phar Lap came to, and 20th Century Fox insisted that the death scenes occur at the end, following the chronology correctly. Wincer, in hindsight, regrets it. In an expressive interview with Cinema Papers in 1984, he said:

“I’m not unhappy with the American version of the film, but the reason John Sexton and I chose to go with Fox was because they’d done a good job with ‘The Man From Snowy River.’ And yet, all Fox wanted to do was spend $300,000 making changes to the film. If we had gone, for example, with Disney, they intended releasing the film in its Australian form.”

The U.S. version was retitled “A Horse Called Phar Lap,” and it fared modestly. Though Phar Lap had lived briefly and died in America, in 1984 the story didn’t resonate. It made little difference that Sexton had recruited actual race-caller Dave Johnson, a legendary broadcaster in the U.S., for the Agua Caliente Handicap.

However, down through the years, “Phar Lap” nuzzled into the affections of American racing fans. Modern attempts, including the lovely “Seabiscuit” and awkward “Secretariat,” demonstrated how far ahead of its time “Phar Lap” was.

In Australia, it was inevitable the film would creep into the same musty legendry of its subject matter. For as long as many can remember, on some channel during Melbourne Cup week, “Phar Lap” will be aired. Racing fans still watch it, swelling with emotion when Shivers barrels down the Flemington straight, or Towering Inferno cocks his head against Tom Burlinson in the final shot, under the newspaper headline “DEAD.” Better yet, there are few in Australian racing that will argue the film’s most famous line of all.

“He wasn’t just a horse. He was the best.”