First run on Sept. 24, 1776, less than three months after the signing of the U.S. Declaration of Independence, the St Leger at Doncaster is the oldest of the five Classic races that form the backbone of the flat season in Britain.

Run over 1 mile, 6 furlongs, and 132 yards, the St Leger is the longest of that classic quintet – the others are the 2,000 Guineas, 1,000 Guineas, Epsom Derby, and Epsom Oaks – and the stamina required to win this famous old race can prove a disincentive for top-level breeders, focused as they are on producing horses to excel over 10 or, at most, 12 furlongs.

Partly on account of that prejudice, the race’s fortunes have waxed and waned over the last few decades. But the race – for which fillies as well as colts are eligible – takes on an extra dimension on the rare occasions when a 3-year-old colt comes to South Yorkshire having won the 2,000 Guineas over one mile at Newmarket in May and the Derby over 1 ½ miles at Epsom early the following month – and thus still in with a chance of achieving that rarest of distinctions, the English Triple Crown. (A 3-year-old filly who wins the 1,000 Guineas, Oaks, and St Leger is considered to have landed the “Fillies’ Triple Crown,” but that feat – last achieved by Oh So Sharp ridden by Steve Cauthen in 1985 – does not have the lure of the male equivalent.)

West Australian in 1853 was the first of only 15 colts to have landed the Triple Crown, and nowadays, with glittering autumn prizes forming a distraction at home and overseas, the treble is rarely attempted. A measure of the enthusiasm of the British racing community to see the feat pulled off once more is that two years ago, a sweltering crowd of 32,000 (around 20 percent higher than normal at the track’s biggest day) packed into Doncaster Racecourse with one thing in mind: To see Camelot, trained in the fabled Co. Tipperary yard Ballydoyle by Aidan O’Brien, become the first horse in more than 40 years to land the Triple Crown.

Sent off 2-to-5 favourite, Camelot was narrowly denied his place in racing’s most select roll of honour, beaten three-quarters of a length by 25-to-1 outsider Encke, trained by Mahmood Al Zarooni – who, within a few months, was to prove the villain of the Godolphin anabolic steroids scandal.

In 1970, 42 years before Camelot’s thwarted attempt at racing immortality, another colt trained by an O’Brien (no relation) at Ballydoyle became the 15th and latest Triple Crown winner, a horse whose name resounds across the decades, an equine superstar whose frailties simply added to his magnetic appeal: Nijinsky.

By August 1968, Vincent O’Brien, master of Ballydoyle, was already garlanded as the nonpareil among the ranks of European trainers. Among his owners was Charles W. Engelhard, Jr., the American minerals tycoon who, it was said, was the model for Goldfinger in the James Bond novel. An owner on a large scale, Engelhard had kept horses with O’Brien for several years, and he asked the trainer to go over to to E.P. Taylor’s Windfields Farm near Toronto to look at a potential yearling purchase, a colt by Ribot.

“I thought, ‘My God, it’s a long way to go to see one horse! But we’d better do it,’” O’Brien recalled. “I saw the horse by Ribot and I didn’t like him a whole lot. In fact, he had a crooked foreleg. Then I thought I’d better see what else they’d got. I saw this other horse and he really filled my eye.”

“This other horse” was a bay colt from the second crop of the great Canadian champion Northern Dancer, and on O’Brien’s recommendation, Engelhard bought the youngster for CAD$84,000 ($77,000) – a Canadian record – at the sales a few weeks later. As pioneer of Northern Dancer blood in Europe, this colt was to prove a pivotal figure in racing history.

On arrival at Ballydoyle, Nijinsky posed a problem.

“When I got him over from Canada,” O’Brien remembered, “we found he wouldn’t eat his oats. We were puzzled and worried as it went on for some days. I called up the manager of Windfields Farm, and he told me the horse had never been offered oats, and had been fed nuts [pellets]. It never struck me that a horse might have been used to eating nuts instead of oats, so I said, ‘Please get some of those nuts over here straight away.’ But the very day they arrived the horse started to eat oats.”

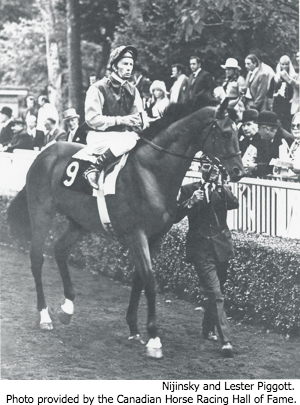

Despite earning a home reputation for non-cooperation – “I am somewhat concerned about Nijinsky’s temperament,” O’Brien wrote to Engelhard, “and that he is inclined to resent getting on with his work” – in 1969, the colt posted an unblemished juvenile record, winning four races at the Curragh before going to Newmarket for the prestigious Dewhurst Stakes, and his first encounter with the man who was to play such a central role in his story. Lester Piggott was not inclined to get emotional about the horses he rode, so his recollection that “with Nijinsky, it really was love at first sight” has a special significance.

(Some years ago, I hosted “An Evening with Lester Piggott” in Newmarket to raise funds for the National Horseracing Museum, and during our interview, I took the opportunity to ask the famously laconic jockey about his first awareness of the colt who figures as one of the very best horses he ever rode. “Had Vincent told you about Nijinsky, that he was something special?” “No, not really.” “Had the lads at Ballydoyle told you about him?” “No, not really.” “Then how did you know about him before riding him in the Dewhurst?” “I read it in the paper.”)

Nijinsky won the Dewhurst easily, and in spring 1970, after winning at the Curragh in the hands of O’Brien’s stable jockey Liam Ward (who rode Nijinsky in all his Irish races), was reunited with Piggott for the 2,000 Guineas, which he won easily from Yellow God.

A few days after the race, Piggott received a letter from Romola Nijinsky, widow of the horse’s balletic namesake, which read:

“I was tremendously impressed with your magnificent winning of the 2,000 Guineas race this afternoon on the beautiful horse Nijinsky, and I send you my congratulations. I ask of you now only one thing – please win the Derby for us!”

Nijinsky did indeed win the Derby for her – and for his rapidly increasing legions of admirers – but he nearly did not run. Unknown to the outside world, the colt had suffered a severe bout of colic the day before the race, and for a while, his participation was in doubt. But he recovered well enough and went off 11-to-8 favourite – the only time in his 13-race career he started at odds against. He won by 2 ½ lengths from the top-class French colt Gyr.

As is customary after the Derby, winning connections were invited up to meet the British royal family, and during the ascent, Engelhard, who was not as thin as Lester Piggott, felt his braces [suspenders] give up the unequal struggle with his morning-suit trousers – and so he desperately clamped his elbows to his sides in order to keep the trousers up in the royal presence. Vincent O’Brien’s widow Jacqueline remembers how the winning owner wriggled about in an effort to maintain his dignity while shaking the royal hand (belonging on that occasion to Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother) – and afterwards Engelhard told her, “If I’d moved my arms, my trousers would have fallen down!”

Nijinsky went on to win the Irish Derby (Meadowville, ridden by Piggott, was runner-up) before cruising clear of 1969 Derby winner Blakeney in the King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes at Ascot, earning a telling tribute from Piggott: “That day he was the most impressive horse I ever sat on.”

Now the debate began. Should Nijinsky be trained for the St Leger in mid-September, when he would surely become the first Triple Crown winner in 35 years since Bahram in 1935? Or should he miss Doncaster and his training programme be focused entirely on preparation for the Prix de l’Arc Triomphe at Longchamp on the first Sunday of October? The Arc was his major autumn target, and victory in Europe’s most prestigious race would guarantee gigantic earnings as a stallion, but the Leger – and thus the Triple Crown – looked there for the taking.

A week after the King George, the debate suddenly seemed academic, for Nijinsky had contracted the virulent skin disease ringworm.

“So much of his hair fell out that he was bald over most of his body,” Vincent O’Brien recalled. “Of course, there was no way we could put a saddle on him. The most we could do was to lead him out and to lunge him a little.”

At the end of August, with the St Leger coming inexorably closer, Nijinsky was still in such a sorry state that he could not be ridden for more than 10 minutes or he would bleed. Going to Doncaster seemed increasingly unlikely, but then came another twist.

Charles Engelhard’s own health was deteriorating – an addiction to Coca-Cola did not help – and well aware that a Triple Crown victory for Nijinsky would bring his owner turf immortality, Engelhard persuaded Vincent to get Nijinsky to Doncaster for the St Leger if he could. And when Nijinsky started showing signs of recovery, his training regime was restructured, with Doncaster the next stop.

As with the colic episode on Derby eve, the O’Brien camp kept very quiet about Nijinsky’s affliction, and at Doncaster, he was considered a stone-cold certainty: the Daily Express headline that morning read: “IT’S NIJINSKY – BAR AN EARTHQUAKE.”

Piggott’s St Leger day did not start well. His first two rides were both warm odds-on favourites – as Nijinsky would be – and both were beaten: Nora’s Choice (backed from 10-to-11 to 4-to-7) was pipped by a short head in the opener, and worse followed in the second race, in which Piggott rode 30-to-100 favourite Leander (trained for Charles Engelhard by Jeremy Tree) against just three opponents. The jockey tells the story:

“As the stalls opened, Leander stumbled and I fell off – upon which half a dozen men suddenly emerged from the nearby trees asking where I had been shot! They were plain-clothes policemen who had been keeping an eye on me all day following a threat telephoned to the racecourse by an escaped inmate of Rampton, the nearby mental institution.”

The police had chosen not to inform Piggott that he was a target, and his mind was soon back on the immediate matter in hand – renewing his acquaintance with Nijinsky in the paddock.

“I had not clapped eyes on him since Ascot, and to my mind the gleam in his eye was a little dimmed, and he seemed quieter than usual as we went through the preliminaries,” Piggot said. Perhaps, thought his jockey, the colt – who started at odds of 2-to-7 – was still feeling the after-effects of his illness.

The race seemed straightforward enough, as Piggott recorded: “He walked sweetly into the stalls, jumped out well and settled. Looking to find any limit to Nijinsky’s stamina, the leaders set a good gallop, and with a mile to go there was only one horse behind us, but the pace was beginning to tell on the front-runners and one by one they fell back.

“With its long, wide home straight, Doncaster is no place for a horse with suspect stamina and I did not want to get to the front too soon, but after the three-furlong marker, I asked Nijinsky to move up, and he steadily sidled past his rivals until hitting the front 300 yards out to a tremendous roar from the crowd. At the post we were a length in front of Meadowville.

“Nijinsky had won the Triple Crown, and the headlines screamed the ease of his victory. Certainly it had looked facile, but the few correspondents who questioned the ease of his win were quite right: However it may have appeared, Nijinsky was all out at the end of the St Leger and could not have won by much further.”

Vincent O’Brien shared Piggott’s opinion: “He won, but I would say he wouldn’t have pulled out any more. Furthermore, he lost 29 pounds in weight coming back from the St Leger.”

Nijinsky’s winning the Triple Crown was a magnificent achievement, but it came at a price.

“The Leger would not have helped his preparation for the Arc,” O’Brien reflected, and 22 days later, Nijinsky was controversially beaten in Paris – his first defeat following 11 successive wins.

For Piggott, the writing had been on the wall before the race.

“Longchamp on Arc day is always packed, but in 1970 it was heaving with people who had come to see Nijinsky,” he recalled. “Too many of these worshippers were inside the paddock, and with camera crews and photographers fighting in a desperate scrum to get shots of the most famous horse in the world on his biggest day, Nijinsky became very stirred up. By the time I walked into the parade ring, he was pouring sweat, and there was a look of panic in his eye.”

The Triple Crown winner was beaten a head by Sassafras, and argument raged about whether Piggott had left too much ground for Nijinsky to make up in the short straight. The rider was characteristically unapologetic.

“Certainly Nijinsky would have won had he not swerved almost in the shadow of the post, and certainly he would have won had his initial finishing run not been blocked on the final bend,” Piggott said.

But no matter how many times you studied the replay of that contentious contest, Nijinsky had been beaten, and with retirement beckoning, Engelhard and O’Brien agreed that the colt should have one more race, in order to end a famous career on a winning note.

Thirteen days after the Arc, Nijinsky was at Newmarket for the Champion Stakes, and again Piggott entered the paddock to an alarming sight.

“The moment I saw Nijinsky in the parade ring, I could tell that he had not got over the Arc experience: He was a nervous wreck, and the huge crowd, which had turned out to bid him farewell, just made matters worse. In the race, he never gave me the old feeling, and when I asked him to go on and win there was precious little response.”

Nijinsky was beaten a length and a half by Lorenzaccio – according to Piggott, “a good horse, but one Nijinsky in his prime could have picked up and carried.”

So Nijinsky’s racing career ended on a resounding down-beat, but at Claiborne Farm in Kentucky, he was to prove one of the great stallions of the modern era, siring a steady stream of top-notch horses including Epsom Derby winners Golden Fleece, Shahrastani, and Lammtarra, plus Kentucky Derby winner Ferdinand (indeed, he remains the only stallion to sire the winners of both the Kentucky and Epsom Derbys in the same year – Ferdinand and Shahrastani in 1985).

Two other winners of the Derby at Epsom, Kahyasi and Generous, were his grandsons, and of the dozens of other top-class horses he sired, mention must be made of O’Brien-trained Royal Academy, whose astounding win in the 1990 Breeders’ Cup Mile at Belmont Park just 12 days after Piggott’s extraordinary return to the saddle was one of the greatest moments of all.

Charles Engelhard, the last man to own a Triple Crown winner, died in March 1971 at the age of 54, and Vincent O’Brien, greatest of all trainers, in June 2009.

Nijinsky himself lived to the good equine age of 25 before he was put down in 1992 on account of worsening health problems.

He was a great racehorse – not perfect, but his imperfections as well as his towering talent ensured his lasting place in the affections of all who saw him run; and especially those who were at Doncaster in September 1970 to see him land the Triple Crown and join racing’s crème de la crème.