By the end of 1948, it was believed there was only one horse in the United States that had any chance of defeating Citation. A world-record holder over a mile, this horse was the first animal in America to crack two minutes for a mile-and-a-quarter. But you probably won’t have heard of him. He’s not in the American Hall of Fame. In fact, he’s not even American. He was Australian, a 1947 California import called Shannon II.

But let’s begin at the end. By November 1948, when Shannon ran his last race in the San Francisco Handicap, there was no horse anywhere that held or shared more world records than he. He had broken watches at Bay Meadows, Hollywood Park, Golden Gate Fields, Tanforan, and Sydney’s Randwick and Rosehill racecourses. He had won the Hollywood Gold Cup and the Argonaut Handicap, broke the hearts of the excellent On Trust and Mafosta, and his earnings were bettered by only Citation that year. Johnny Longden said he had never been astride a faster horse. Just who was he?

Shannon was foaled in the New South Wales Hunter Valley in the spring of 1941. His sire, Midstream, was a son of Blandford, and his dam, Idle Words, was by the champion stallion Magpie. Their union was then unremarkable. The Blandford line was new to Australian breeding, and Shannon was dropped from only the second crop of Midstreams. But though plain and small, he proved far from unremarkable. In five seasons of Sydney racing, Shannon was peerless.

He won the Epsom Handicap, King’s Cup, and George Main Stakes (twice), sometimes a length in hand, sometimes six. He defeated horses such as Flight and Tea Rose in an era marked by heroes including Bernborough, and he was quick. Crazy quick. Shannon’s unofficial time in the 1946 Epsom mile (1:32.5) still stands at Randwick, as does a seven-furlong record at Rosehill. By the time he came up for sale in 1947, he was a rising 7-year-old but remarkably preserved. He had raced only 25 times.

Shannon’s sale to the U.S. followed a trend of Australian bloodstock steaming its way to American farms at that time. Beau Pere, Ajax, Bernborough et al had all found stud careers in America. But Shannon was to tread new territory. He wasn’t sold to stud; he was sold to race, and he became the first Australian Thoroughbred to infiltrate the highest levels of American horse racing.

Purchased first by catering king Harry Curland, Shannon ended up in the hands of Hollywood attorney Neil McCarthy. Curland’s exit from the ownership was no accident. Shannon had barely touched foot in California in November 1947 when The Jockey Club deferred his registration. There was a flaw in his pedigree, they declared. It occurred 11 generations back, in 1823 or so, and U.S. racing flew into a flap. The Blood-Horse, Daily Racing Form, even the New Yorker, weighed in on the issue. And the problem went all the way back to the Jersey Act. When the issue was finally resolved, Neil McCarthy had himself a heck of a famous racehorse.

Shannon’s first months in California were a disaster. Placed into the Bay Meadows barn of Willie Molter, the Hall of Fame trainer just didn’t get it. Shannon was a puzzle, had a running style unknown to Molter’s other charges. And Johnny Longden didn’t fare much better. Asking Shannon to run from the front, the jock got nothing from the famous Australian. Shannon hung on the turns, choked in the straights, and became a laughing stock across California. It would take him six months to win a race.

In May 1948, at the coming around of the Hollywood Park meeting, Molter slung a new jockey into Shannon’s irons and found himself a different horse. Johnny Adams, and later Jack Westrope, rode the horse as he had been ridden in Sydney – sit back and sprint later. And Shannon unfurled. The Argonaut, Hollywood Gold Cup, Forty-Niners, Golden Gate, and San Francisco handicaps... the Australian swept them all. Nine-furlong records, 10 furlongs, they all tumbled. They called him “the bullet from Down Under” and, when it came to a proposed match race with Citation, “the white hope of the West Coast.” But the match race never occurred. Shannon was retired in November 1948, champion older horse of his year.

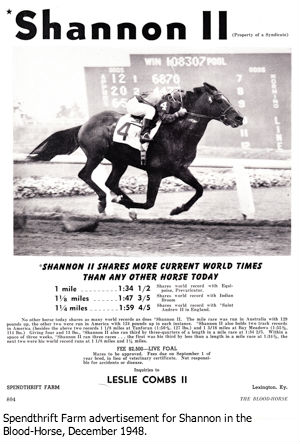

He was syndicated and sent to Spendthrift Farm. Leslie Combs II had much to advertise. Shannon was arguably the most decorated horse in the stallion barn, commanding $2,500 a service, bettered only by his lofty neighbour, Alibhai. And his books were good. Both Combs and McCarthy sent their own mares to Shannon, and he produced 132 foals of racing age. One hundred nineteen made it to the racetrack, of which 100 were winners. But the blue-chip progeny were rare. Shannon produced only six stakes winners before he died in 1955.

Of this six, Clem, out of the Supremus mare Impulsive, was the best. From 1957-58, he won the Arlington Classic, Woodward Stakes, the Withers, Washington Park, and United Nations handicaps. He lost the Toboggan and Suburban when he ran into Bold Ruler, but on three other occasions in the space of a month, Clem accounted for Round Table. And the son of Shannon continues to make his presence felt. Clem is the great-great-great-great-grandsire of the 2013 Victoria Derby winner Polanski.

Shannon’s stud record did not reflect his racing record. He was a far better racehorse than stallion. The famous Australian lies in an unmarked grave at Spendthrift Farm, and although a plaque commemorating his name was recently added to the stallion barn, Shannon seemed to drift off into the hot twilight of memory after his death. But, pull out his life and you’re met with an extraordinary story, one of racing fame in two hemispheres. It was a pioneering life that reads stranger than fiction, and it begs the question: How did we manage to forget him?

---

Jessica Owers is the author of Shannon: Before Black Caviar, So You Think or Takeover Target